The setting is luxurious: a Hilton Hotel that evidently does a large conference business. Everything about the conference is first-class: the meeting rooms, the lunch, the audio-visual presentations – and, it costs me nothing. All expenses are paid. I’ve been very impressed by what the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society does, by way of educational and support services for cancer survivors and their families, and this event is no exception.

We start off with a biology lecture by Dr. Martin Carroll, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, that leads me to look at blood cancers in a new way. Here are a few insights from that talk (the description “blood cells” refers to lymphocytes – the cells that circulate through the lymphatic system – as well as to the red and white cells we normally think of as blood cells):

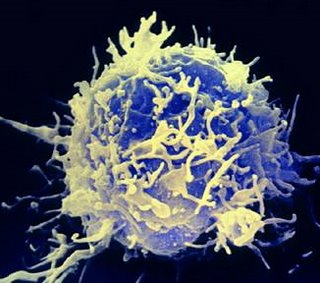

We start off with a biology lecture by Dr. Martin Carroll, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, that leads me to look at blood cancers in a new way. Here are a few insights from that talk (the description “blood cells” refers to lymphocytes – the cells that circulate through the lymphatic system – as well as to the red and white cells we normally think of as blood cells):“Cancer cells are blood cells that forget to die.” Blood cells grow out of stem cells. While stem cells live a very long time, once they change into blood cells, they have a very limited lifespan. Blood cells are constantly dying and being replaced. Once blood cells mutate into cancer cells, however, they retain some of the long-lifespan characteristics of stem cells. This is a problem – because, in the normal order of things, these cells would need to die to make room for new cells that are being created. Instead, the mutated cells hang around and cause problems.

“A stem cell can make a new blood cell in about two weeks.” This is the reason for the three-week interval between chemotherapy treatments. Once the chemo drugs kill cancer cells, the body mistakenly tries to replace them, by transforming more stem cells into cancer cells. It sounds to me a bit like “Space Invaders,” the primitive video game we used to play in the arcades, as kids: you shoot down a row of creepy-looking aliens, only to see another rise up in their place and start marching ominously toward you.

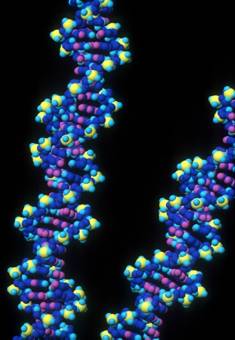

“The body makes few mistakes.” We have trillions of blood cells, but only a few ever turn cancerous. In order to manufacture a single blood cell, about three billion DNA molecules are required – and the vast majority of these DNA molecules are manufactured absolutely correctly.

“Just because it’s a genetic disease doesn’t mean you got it from your parents.” There are inherited DNA mutations, and there are acquired DNA mutations. Because they’re not transmitted by mutated sperm or egg cells, blood cancers are acquired, not inherited.

“When pathologists examine slides, there must be millions and millions of malignant cells in the body before they even start detecting them.” At the time when cancer is first diagnosed, the first mutation probably began months, and even years, before. It was only when the numbers of malignant cells got well into the millions that they began to show up on the pathologists’ radar.

“It’s the proteins that arise out of DNA and RNA that cause blood cancers.” An oncogene is a protein that can cause blood cells to grow, bypassing their normal regulatory mechanisms. When we discover the genetic abnormality at the root of cancer, we can attack the protein with certain, targeted medications that aim directly for the protein. Rituxan – the drug I received along with my chemotherapy medications – is one of these new, targeted therapies.

“Lymphatic cells are extremely complicated.”

Unlike other blood cells, which are relatively straightforward, lymphatic cells are much more complex, and are therefore hard to study.

“Chemotherapy drugs did not arise out of molecular biology.” They were developed based on empirical observation. World War I- and World War II- era doctors noticed that soldiers that had been exposed to mustard gas developed abnormalities in their bone-marrow cells and lymph nodes. This led them to experiment with mustard-gas derivatives to fight lymphoma, which is a disease of lymphatic cells grown too large. Cytoxan – one of the chemo drugs I received as part of the CHOP combination – is derived from mustard gas.

“Lymphocytes are the generals of the lymphatic system.” (This one comes not from Dr. Carroll’s keynote address, but from a workshop on aggressive lymphomas, led by another Penn cancer physician, Dr. Babis Andreadis.) When there’s an infection, the body calls in the generals – the lymphocyte cells – to scope out the situation and decide what to do. In a healthy system, the lymphocytes (“the generals”) then call in the white blood cells, which are like the foot soldiers in the battle against infection. The lymphocytes tend to congregate in the lymph nodes, which – when cancer transforms them into too-large cells that live too long – causes a population explosion in the lymph nodes, which causes swelling. That swelling of the lymph nodes is often the first hint patients have that something is not right – and by then, the cancer is already far-advanced, because of what has been happening for some time on the microscopic level.

“Lymphocytes are the generals of the lymphatic system.” (This one comes not from Dr. Carroll’s keynote address, but from a workshop on aggressive lymphomas, led by another Penn cancer physician, Dr. Babis Andreadis.) When there’s an infection, the body calls in the generals – the lymphocyte cells – to scope out the situation and decide what to do. In a healthy system, the lymphocytes (“the generals”) then call in the white blood cells, which are like the foot soldiers in the battle against infection. The lymphocytes tend to congregate in the lymph nodes, which – when cancer transforms them into too-large cells that live too long – causes a population explosion in the lymph nodes, which causes swelling. That swelling of the lymph nodes is often the first hint patients have that something is not right – and by then, the cancer is already far-advanced, because of what has been happening for some time on the microscopic level.After the keynote address, I notice Dr. Carroll standing by himself, off to one side of the room. I go up to him and ask a question about my particular type of NHL, “diffuse mixed large and small cell.” He tells me this type sits on the borderline between indolent and aggressive lymphomas. I have some of both types of lymphoma cells: the smaller, indolent cells, and the larger, aggressive ones. This means I have the worst of both worlds. Large-cell, aggressive lymphomas are more immediately dangerous, because they are fast-moving – although, with treatment, they can often be cured completely. Small-cell, indolent lymphomas, on the other hand, are less of an urgent situation, but are very hard to defeat completely, staging slow-motion comebacks over time. People like me, who have this borderline type, must be treated quickly, with often-harsh chemo regimens; yet, we’re also unlikely to be cured, due to the small-cell component of our disease. Instead, the small-cell component must be managed over time – much as a chronic disease like diabetes is managed.

I find these simple explanations – designed for people like me, without much science background – to be extremely useful. I enjoy the conversations over lunch, as well. I’ve come to the conference by myself, but when I get talking to my neighbors – who are cancer patients and family members of cancer patients – I find we have a lot in common.

I stick around for an afternoon workshop session as well, but find that to be less helpful. The workshop, billed as “Cultivating Spiritual Well-Being,” is led by a hospital chaplain. It’s the only topic on the program that has anything approaching a theological dimension. I find, though, that the leader is trying so hard – “bending over backwards” would be more accurate – to be respectful of religious diversity and not to offend anyone, that she ends up saying very little of substance. Her talk is on the difference between “spirituality” and “religion”: she’s holding fast to the idea that it’s possible to be “spiritual but not religious,” as many in our culture claim they are.

I don’t buy it, and never have. To me, if you try too hard to reduce religious faith to a least common denominator, what you end up with is the smallest denominator of all: zero. And “zero” is about what I get out of the speaker’s Power Point presentation on spirituality. It’s too bad, because she strikes me as a caring person, and probably a very fine chaplain, when it comes to one-on-one encounters with hospital patients. She proves to be a pretty good facilitator, as well, when we reach the time of discussion at the end. Yet it’s impossible to tell, from her presentation, what her own religious background is.

I would have liked to have known. I’ve always believed that the most fruitful ecumenical or interfaith discussions happen when two people of different traditions sit down and share who they are, practicing careful listening and respectful questioning. The chaplain could have been a Presbyterian, for all I know, or she could have been a Buddhist – but, either way, I felt deprived of hearing whatever it was she’d recommend, by way of spiritual practices that come from her own tradition. And that’s a shame.

I would have liked to have known. I’ve always believed that the most fruitful ecumenical or interfaith discussions happen when two people of different traditions sit down and share who they are, practicing careful listening and respectful questioning. The chaplain could have been a Presbyterian, for all I know, or she could have been a Buddhist – but, either way, I felt deprived of hearing whatever it was she’d recommend, by way of spiritual practices that come from her own tradition. And that’s a shame.All in all, it’s a good and useful day – well worth the long drive to Philadelphia and back.

1 comment:

Carl,

After my husband was diagnosed with leukemia, we too found how how diverse these blood diseases are. I would have like to hear more about his specific type at the time...didn't have the opportunity. Information is important, can't have too much of it!

Rosemarie

Post a Comment