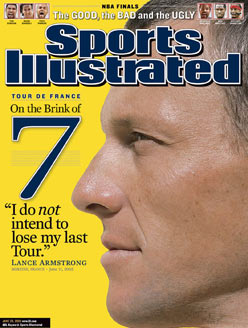

Yesterday, as I drove back from the blood-cancer conference in Philadelphia, I was listening to a book-on-tape of Lance Armstrong’s autobiography, It’s Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life (New York: Putnam’s, 2000). Lance, of course, is the world-champion cyclist who recovered from testicular cancer that had spread to his lungs and his brain, going on to win seven Tour de France bicycle races.

Something Lance wrote, about the weeks and months immediately following his cancer treatment, struck me as true to my experience. After a herculean struggle that included an exceptionally harsh chemotherapy regime, as well as surgery to remove a testicle and cancerous growths on his brain, Lance found it hard to take up the tasks of his former life again. For him, of course, that meant training as a competitive cyclist.

The French-sponsored cycling team of which he was a member had removed him from their roster, for medical reasons. His former corporate sponsors had all dropped him, assuming his career was finished. He was cashing monthly disability-insurance checks that would keep him financially comfortable for the next five years, without his having to lift a finger. Although he had had some success in light physical training, most people assumed Lance Armstrong would never again be a contender in the world of competitive cycling.

The French-sponsored cycling team of which he was a member had removed him from their roster, for medical reasons. His former corporate sponsors had all dropped him, assuming his career was finished. He was cashing monthly disability-insurance checks that would keep him financially comfortable for the next five years, without his having to lift a finger. Although he had had some success in light physical training, most people assumed Lance Armstrong would never again be a contender in the world of competitive cycling.Lance knew that, if he entered another race, Lloyd’s of London would immediately cut off his disability payments, and he had no guarantee he would ever make it back to the top of the cycling game, where the big money was. Yet there was a part of him that knew he had to take that risk.

Even so, he found it hard to get started. He procrastinated, whiling away his days playing golf with friends. It was hard to move forward, as a cancer survivor:

“But how do you survive cancer? That’s the part no one gives you any advice on. What does it mean? Once you finish your treatment, the doctors say, You’re cured, so go off and live. Happy trails. But there is no support system in place to help you to deal with the emotional ramifications of trying to return to the world after being in a battle for your existence.

You don’t just wake up one morning and say, ‘Okay, I’m done with cancer, and now it’s time to go right back to the normal life I had.’... I was physically recovered, but my soul was still healing. I was entering a phase called survivorship” (p. 186)

I’m not even physically recovered yet, but already I can see the challenges before me. I’m not the same person I was, before beginning treatment. There are days when I feel unaccountably angry, recalling the things I’ve had to go through. There are other days when I have no patience whatsoever with the little things, the minutiae of running a church. There are times when I even miss the freedom of my sick days – when I felt lousy, physically, but could spend my time however I wanted to.

When Lance and his then-wife, Kik, finally did rent an apartment in France and he began entering bicycle races again, he found it hard to marshal the enthusiasm, the competitive drive, that had once propelled him:

“My own attitude wasn't as good. Things weren't going so well for me on the road, where I had to adjust all over again to the hardships of racing through Europe. I had forgotten what it was like. The last time I’d been on the continent was on vacation with Kik, when we’d stayed in the best hotels and played tourists, but now it was back to the awful food, the bad beds in dingy road pensions, and the incessant travel. I didn't like it.

“My own attitude wasn't as good. Things weren't going so well for me on the road, where I had to adjust all over again to the hardships of racing through Europe. I had forgotten what it was like. The last time I’d been on the continent was on vacation with Kik, when we’d stayed in the best hotels and played tourists, but now it was back to the awful food, the bad beds in dingy road pensions, and the incessant travel. I didn't like it.Deep down, I wasn’t ready. Had I understood more about survivorship, I would have recognized that my comeback attempt was bound to be fraught with psychological problems. If I had a bad day, I had a tendency to say, ‘Well, I’ve just been through too much. I’ve been through three surgeries, three months of chemo, and a year of hell, and that's the reason I'm not riding well. My body is just never going to be the same.’ But what I really should have been saying was, ‘Hey, it’s just a bad day’” (p. 188).

I’m moving further into this phase called “survivorship.” And, like Lance, I’m finding there aren’t so many road signs to mark the way. I’ve grown quite used to the routine of going into Dr. Lerner’s office for my weekly blood tests, and having the nurses inquire into minute details of my health and physical condition. Now, the doctor has said, “You’re doing fine, see you in three months.” My only trip into his office will be once a month, to have my porta-cath flushed. I’m gradually moving back into full-time ministry – although, frankly, there are days when I still don’t feel up to it.

I’m learning, as Lance did, that there’s a gap between active medical treatment for cancer and full recovery. As for how we scope out a path across it, most of us cancer survivors are left to our own devices.

No comments:

Post a Comment