Bone pain. Vanessa in Dr. Lerner's office told us it affects some NHL patients more than others. Now it's here.

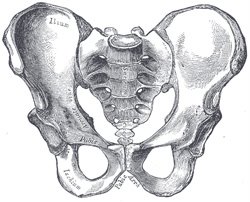

It awakens me in the wee hours of the morning. It's a dull ache – more of a nagging pressure, really, than any actual pain. I feel it right where Vanessa predicted I would: in the pelvis and femur, the largest bones of the body, the places where there are the largest concentrations of marrow.

The marrow-filled centers of these thick bones are the body's blood-cell factories. The Neulasta shot I had on Friday is supposed to jump-start the production of white blood cells, and that – I hope and pray – seems to be exactly what's happening.

The silence of the cavernous, World War 2 aircraft factory is shattered, as the foreman throws the switch on the mercury-vapor lamps that sizzle for a moment, then burst into light. The doors crash open, and hordes of third-shift Rosie the Riveters pour in, clad in their overalls, to keep the B-29s rolling off the assembly line around the clock. It's an ungodly hour to be working, but there's nothing to be done about it. There's a war going on – a war against cancer.

The silence of the cavernous, World War 2 aircraft factory is shattered, as the foreman throws the switch on the mercury-vapor lamps that sizzle for a moment, then burst into light. The doors crash open, and hordes of third-shift Rosie the Riveters pour in, clad in their overalls, to keep the B-29s rolling off the assembly line around the clock. It's an ungodly hour to be working, but there's nothing to be done about it. There's a war going on – a war against cancer.Yes! I say to myself, as I shift position in bed, trying to get more comfortable. The treatment's working. The war birds are rolling off the assembly line. The white blood cells are under construction.

I'm developing a somewhat different attitude towards pain as I journey, day by day and night by night, through this disease. Normal thinking is turned on its head. It's not the lymphoma that's causing me the pain, fatigue and nausea. It's the treatment.

The lymphoma is a wily, stealth attacker, silently soaring without lights like some teflon-covered spy plane, insinuating itself into my very DNA. It's not the assailant, but the treatment the doctor's administering to fight the assailant, that's making me uncomfortable.

The lymphoma is a wily, stealth attacker, silently soaring without lights like some teflon-covered spy plane, insinuating itself into my very DNA. It's not the assailant, but the treatment the doctor's administering to fight the assailant, that's making me uncomfortable.I'm a relatively unusual NHL patient, in that my disease was diagnosed accidentally, before I'd developed any symptoms. As we first sat down with Dr. Lerner to talk about chemotherapy, I was very much aware that I'd been walking around performing all my normal activities. Sure, in retrospect I could recall that something hadn't been right for a while – I'd been feeling a little tired, and I was getting concerned about a vague, tight feeling in my abdomen (the same feeling that could have subconsciously inspired me to ask Dr. Cheli, our family physician, about an aortal aneurysm) – but these feelings were barely on the radar screen for me. They weren't interfering with my life.

Yet in signing up for a treatment regime that includes the surgical insertion of what is, essentially, a high-tech funnel so noxious chemicals can be poured into my body, altering the fundamental structure of my cells, I was volunteering for hardship duty.

And so, when the pain comes, I take it as a sign that I'm getting better. Any other pain would be exactly the opposite. The lingering pain from my porta-cath surgery, for example, is slowly diminishing day by day. When I stand in the shower and lift my right arm, I can feel the swollen scar tissue pulling. Yet, with each day that goes by, the pain from that wound is incrementally less, and I celebrate its diminishment.

And so, when the pain comes, I take it as a sign that I'm getting better. Any other pain would be exactly the opposite. The lingering pain from my porta-cath surgery, for example, is slowly diminishing day by day. When I stand in the shower and lift my right arm, I can feel the swollen scar tissue pulling. Yet, with each day that goes by, the pain from that wound is incrementally less, and I celebrate its diminishment.Not so with the bone pain, nausea and fatigue brought on by the chemotherapy. As each day unfolds, bringing me closer to my nadir point ten or eleven days after receiving the drugs, the discomfort can be expected to increase. While I dread the mounting side effects because of the way they'll make me feel, there's also a part of me that wants to cheer their progress.

It's a kind of therapeutic pain – and therefore, it defies the usual logic of pain. I need to go through this, I tell myself. I need to endure it. It's going to make me well.

In one of the strangest and most oddly beautiful poems ever written in the English language, the Elizabethan-era Anglican priest John Donne invites God into his life with an almost masochistic glee – not to comfort him, but to assault him:

"Batter my heart, three person'd God; for, you

As yet but knocke, breathe, shine, and seeke to mend;

That I may rise, and stand, o'erthrow mee, and bend

Your force, to breake, blow, burn and make me new."

Donne ends his poem by saying,

"Divorce mee, untie, or breake that knot againe,

Take mee to you, imprison mee, for I

Except you enthrall mee, never shall be free,

Nor ever chast, except you ravish mee."

(From Holy Sonnet XIV)

It's the sort of twisted, Mobius-strip logic a cancer survivor would understand.

3 comments:

Carl,

I have read that yoga and acupuncture can be helpful in managing chemotherapy side effects. Maybe one of these modalities might be useful, especially for the nadir days?

Other than labor and childbirth, I have not personally been challenged with extreme physical pain (and those are not comparable to the chronic and increasing discomforts of chemo that you describe), but when Mary was going through treatment for acute leukemia over 25 years ago, she used Lamaze breathing to help in handling the pain of bone marrow treatments. I guess Lamaze could be seen as somehow similar to some of the meditative practices such as used by St. Theresa (the Little Flower) and in some Buddhist traditions. I have heard that some types of music also help some people to relax, focus, and endure. I think your reflections and prayer are similar types of meditations.

I'll be thinking of you over the next couple days, in hopes that the anticipated nadir will be as gentle and shortlived as possible.

Yours in Spirit,

Love, Dotsy

On my homeward bound leg of a trip I took in October, I saw a person wearing a t-shirt in the Charlotte airport that said. "Pain is weakness leaving the body." I associated that saying with fitness training or the like, but it certainly applies to you. Wanna t-shirt? MB

"Pain is weakness leaving the body." I like it. That one's a keeper!

Post a Comment