I’ve had so many wonderful contacts, in recent days, from friends like Anne – people with whom Claire and I were once very close, but from whom we’ve drifted away. It’s an inevitable process, I suppose. The years go by, geographic separation takes its toll, children come along and the sheer dailyness of life piles up all around us like mine tailings. Under the cumulative weight of such pressures, it’s all too easy to let significant friendships dwindle into a dormant state.

The news of my illness has been like a gentle breeze blowing across the sputtering flame of some of these neglected relationships. I’ve discovered that the caring and concern we once took so much for granted are still very much present. We can fan the flame. We can pick up where we left off. And that’s been a great source of strength.

The news of my illness has been like a gentle breeze blowing across the sputtering flame of some of these neglected relationships. I’ve discovered that the caring and concern we once took so much for granted are still very much present. We can fan the flame. We can pick up where we left off. And that’s been a great source of strength.I’m realizing that, for many of these friends, I’m the first of their peers to come down with a life-threatening illness. I’m 49 years old: firmly ensconced in mid-life, but still not so old that casual conversations naturally turn to subjects like heart catheterizations and prescription drug plans. People in their forties aren’t supposed to get cancer. Not only does it seem unfair, but in some way it even seems illogical.

I am of the generation that swayed, in blue jeans worn out at the knees, to the words of Ecclesiastes, chapter 3, as sung by the 1960s folk group, the Byrds:

“For everything,

(turn, turn, turn)

there is a season,

(turn, turn, turn)

and a time for every matter under heaven.

A time to be born, a time to die...”

What were we thinking, as we nodded our heads to that lyrical melody on Top 40 radio? Did we have any conception of what those words mean – of how dark and brooding is their theology?

“What gain have the workers from their toil?” implores Qoheleth, “The Teacher” (Ecclesiastes 3:9). He really wants to know. What is life for, he muses, if it can come to an end so capriciously? Overwhelmed by this mystery, seemingly too deep for human understanding, he concludes, “there is nothing better for them than to be happy and enjoy themselves as long as they live; moreover, it is God’s gift that all should eat and drink and take pleasure in all their toil” (12-13). It’s not all that different from the sappy sentiment of that old beer commercial: “You only go around once in life, so you’ve got to grab for all the gusto you can.” The only difference is that, for Qoheleth, God’s the one working the beer tap.

“What gain have the workers from their toil?” implores Qoheleth, “The Teacher” (Ecclesiastes 3:9). He really wants to know. What is life for, he muses, if it can come to an end so capriciously? Overwhelmed by this mystery, seemingly too deep for human understanding, he concludes, “there is nothing better for them than to be happy and enjoy themselves as long as they live; moreover, it is God’s gift that all should eat and drink and take pleasure in all their toil” (12-13). It’s not all that different from the sappy sentiment of that old beer commercial: “You only go around once in life, so you’ve got to grab for all the gusto you can.” The only difference is that, for Qoheleth, God’s the one working the beer tap.Perhaps Qoheleth’s darkest moment comes in these words: “I said in my heart with regard to human beings that God is testing them to show that they are but animals. For the fate of humans and the fate of animals is the same; as one dies, so dies the other. They all have the same breath, and humans have no advantage over the animals; for all is vanity. All go to one place; all are from the dust, and all turn to dust again” (18-20).

There have been times when I’ve wondered why these gloomy words are in the Bible at all. What is it about the philosophical meanderings of this tortured soul that led the compilers of the Hebrew canon to declare them holy scripture?

Our friend Anne seems for a moment to be on the same page as Qoheleth:

“For me (and I wonder if it is this way for you) the real sticking point is trying to figure it out. The ‘Why?’ As a person of religion and philosophy I’m sure you are well versed at pondering completely unanswerable questions. But now you are at the very center of the question. While our nature is to seek and find meaning in our human experiences and existence, our frustration is most often simply increased as questioning often leads us to even murkier waters.”

But Anne’s got a lot more going for her, faith-wise, than old Qoheleth apparently did:

“It is in the struggle with these questions, however, that the love and support of family and friends, the fellowship of others is most reassuring. If it is not more powerful than the chemicals we have designed to fight disease, it is at its very simplest, more sustaining and meaningful for sure. I know I feel comforted that on some level the inherent goodness of us as human beings is more important, more powerful and more significant than my life and my life’s work could ever be on their own. For me, faith is most tangible as a belief in God’s work through humankind.”

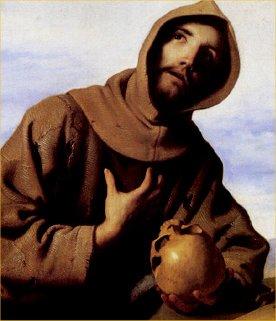

There’s an old story about Francis of Assisi. One day he informed his fellow friars that he intended to go into a nearby village on a preaching mission. He invited one of the novices to accompany him. On their way, they passed several poor, homeless folk who were in need, and each time, Francis stopped to help.

There’s an old story about Francis of Assisi. One day he informed his fellow friars that he intended to go into a nearby village on a preaching mission. He invited one of the novices to accompany him. On their way, they passed several poor, homeless folk who were in need, and each time, Francis stopped to help.So it went, all through the day: one interruption after another. The sun was low in the sky when Francis told his companion it was time for them to return for evening prayers. But the young man objected: “Father, I thought you said we were coming into town to preach to the people.”

Francis only smiled. “My brother, that’s what we have been doing all day.”

On another occasion, Francis puts it even more succinctly: “Preach the gospel at all times. When necessary, use words.”

Thank God for friends like Anne, who reach out across the years with words of caring and concern: words that point to a God of love, who really does care about chemotherapy and white blood-cell counts, about comfort and friendship, about life and death!

No comments:

Post a Comment