Today I come across a link to

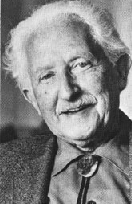

a blog written by another cancer survivor (brain, spinal and lung cancer). Leroy Sievers is his name, and he’s a writer and journalist – having worked for CBS News and ABC News. At one time, he was the executive producer of the

Nightline television news program. Now he’s keeping a cancer diary much like this one, for National Public Radio.

Here’s something Leroy has written, reflecting on his last year or so of living with cancer:

“My body has changed in some ways that are obvious, and in others that aren't. I have a ridge in my skull where they cut it open to take out the brain tumor. You can feel the screws in the plates that hold my skull together. I'm heavier than I'd like to be. I put on weight when I was on steroids, and I haven't been able to work out much the last year. I hate the extra weight, though my doctors seem to think it's healthy.

“My body has changed in some ways that are obvious, and in others that aren't. I have a ridge in my skull where they cut it open to take out the brain tumor. You can feel the screws in the plates that hold my skull together. I'm heavier than I'd like to be. I put on weight when I was on steroids, and I haven't been able to work out much the last year. I hate the extra weight, though my doctors seem to think it's healthy.

Emotionally? Over the past year, I've hit the depths of sorrow, thrown in a little anger, too. Some hope, but probably not as much as I should have. Frustration. The whole gamut of human experience. And maybe that's one of the lessons here. In spite of the cancer, in spite of what we all go through, in the end, we're all just human. We're like everybody else. Except that we're not.

I try to make the most of my life these days. But I was really trying to do that before my diagnosis, too. My view of the future is a little cloudier; it's no longer open-ended. Not everything is possible anymore. I'm pretty much an optimist still, but that has been seriously tested, too.”

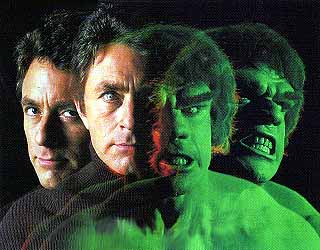

I’m interested to hear that Leroy mentions anger. I’m getting in touch with the fact that anger is an issue for me right now – sort of a delayed reaction to what I’ve been through.

During my chemotherapy, I simply didn’t have time for anger. I had to marshal all my emotional resources in the service of just getting by. The reality is, I’ve probably been stuffing my anger about the cancer for some considerable time. When I received first one clean PET/CT scan report, then another (in late May and early September) that was no time for feeling angry, either. I was supposed to feel relieved (and one part of me did, of course).

So what happens to all that suppressed anger? The answer seems to be that it’s coming out, inappropriately. I find I have a short fuse, these days, for petty frustrations. Other people around me have noticed it, too (in truth, they picked up on it before I did). It’s as though there’s a little voice in my head that keeps whispering, “You shouldn’t have to put up with this nonsense: you have cancer!”

I’m finding ways to procrastinate on things I should be doing – like dealing with the accumulated mail at home (comprised, still, of way too many medical bills and insurance statements, that only serve to remind me of my medical condition). Last month, I found it hard to get our 2005 income tax information to the accountant – tackling that job only at the last minute, just a day or two before the mid-October deadline for the extension I’d filed for last spring. Procrastination, of course, is a classic passive-aggressive reaction.

I have the most energy for creative endeavors, like writing and preaching. Having crashed hard into the brick wall of life’s limited duration, it’s as though the things that matter most to me are the things I create, things just may live beyond me. (Maybe, too, that’s why I felt so determined to apply for additional life insurance, during last week’s open-enrollment period.)

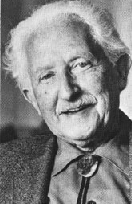

It’s possible that my cancer has bumped me up an adult-development stage. Back in seminary, we learned about

psychologist Erik Erikson’s stages of adult development. The last three of his eight stages – with the typical ages and the challenges and tasks people typically face at those ages – can be described as follows:

Stage Six, Young Adulthood: 18-40 years, intimacy vs.isolation, love relationships

Stage Seven, Middle Adulthood: 40-65 years, generativity vs.stagnation, parenting

Stage Eight, Maturity: 65 years until death, integrity vs.despair, acceptance of one's life

According to Erikson, the 40s and 50s are the prime time for “generativity” – for creating that legacy we’ll leave behind when we die. What happens, I wonder, when a disease like cancer threatens to move the termination-point of life up a decade or two, or three? Does it mean, in my case, that cancer has abruptly shoved me forward, existentially-speaking, from “Middle Adulthood” into “Maturity” – way before I feel ready to be there? If that’s what I’ve been feeling (or, at least, worrying about), then it’s no wonder I’m feeling a bit angry. It’s the psychological equivalent of “the bends” – what scuba divers get when they surface too quickly.

How I sort all this out, I’m not sure. It’s clear that, remission or no remission, I’m still living with cancer, in an emotional sense.

Today, riffling through a pile of accumulated mail, I come upon a terse letter from someone who works for the Board of Pensions of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). It reads as follows:

Today, riffling through a pile of accumulated mail, I come upon a terse letter from someone who works for the Board of Pensions of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). It reads as follows:

The teenage driver laid out in the casket in the funeral home is obviously so much more than a statistic. The teary-eyed family members – eager to reminisce, as though spinning tales would bring their loved one back to life – know that very well. Yet, to some anonymous actuary running his or her finger down a long column of numbers, that makes little difference. Do the numbers breathe? Do they laugh? Do they cry?

The teenage driver laid out in the casket in the funeral home is obviously so much more than a statistic. The teary-eyed family members – eager to reminisce, as though spinning tales would bring their loved one back to life – know that very well. Yet, to some anonymous actuary running his or her finger down a long column of numbers, that makes little difference. Do the numbers breathe? Do they laugh? Do they cry?