It’s a gray, rainy day today, and I’m thinking about something I usually don’t spend much time thinking about: my hair.

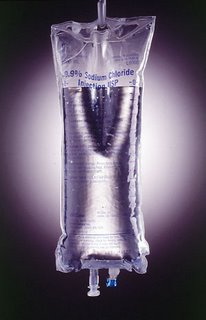

For the past several days, I’ve been on the alert for signs that the predicted, chemotherapy-induced hair loss may be starting. Still no hairs on the pillow or in the bathtub drain this morning – but as I’m toweling off after my shower, my hair feels different. The only way I can describe it is to say it feels like I’ve been swimming in a pool with way too much chlorine. It feels kind of stiff and dry, and my scalp itches.

Maybe it’s just a bad hair day... but somehow, I don’t think so.

A little later, I seriously consider going to the barber shop for the buzz-cut I’ve planned to get, but decide to wait till tomorrow. Or maybe the next day...

Like many guys, I’ve never considered myself to be especially vain about my hair. I’ve had the same basic, low-maintenance hair style for years. If anything, I tend to go a little too long between haircuts – just because I consider fussing with my hair to be a bother.

Like many guys, I’ve never considered myself to be especially vain about my hair. I’ve had the same basic, low-maintenance hair style for years. If anything, I tend to go a little too long between haircuts – just because I consider fussing with my hair to be a bother.I’ve never worried too much about baldness, either. I always figured, if it happens, it happens (so far, I’ve been pretty fortunate). But the prospect of losing my hair all at once feels very different. It’s a visible symbol of change.

It means that – especially if I lose my eyebrows as well – everyone I meet will know that I’ve got cancer, and am receiving chemotherapy. I’m not keeping my condition a secret – but on the other hand, I’m not walking around town wearing a sign that says, “Cancer Patient,” either. Will my hair loss change the way strangers deal with me? Will I become not “that guy over there,” but “that poor guy over there with cancer”?

The most famous guy in the Bible who lost his hair was Samson. Samson was a nazirite – a sort of wild and woolly holy man (literally!). The chief distinguishing feature of nazirites was that they never cut their hair (Judges 13:5).

Samson’s long hair is a symbol of his devotion to God, and also the source of his power. While most film and literary treatments of Samson have portrayed the hair-and-power connection as something magical, the biblical writers probably saw it more as symbolic of the strength of his spiritual life. As long as Samson keeps his austere, ascetic ways, the Lord is with him; but once he adopts the settled ways of townsfolk and comes to enjoy his creature comforts a little too much, he ceases to be able to perform those feats of prodigious strength – like catching three hundred foxes and tying their tails together (Judges 15:4), or slaying a thousand warriors with the jawbone of a donkey (15:15). It’s pretty colorful stuff – not to mention grisly, at times – but this is a sort of Paul Bunyanesque tall tale, so I think we can forgive the storytellers a little poetic license.

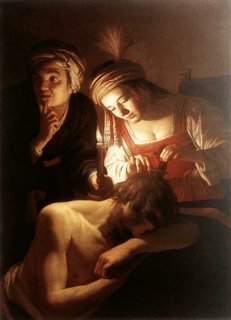

Samson’s long hair is a symbol of his devotion to God, and also the source of his power. While most film and literary treatments of Samson have portrayed the hair-and-power connection as something magical, the biblical writers probably saw it more as symbolic of the strength of his spiritual life. As long as Samson keeps his austere, ascetic ways, the Lord is with him; but once he adopts the settled ways of townsfolk and comes to enjoy his creature comforts a little too much, he ceases to be able to perform those feats of prodigious strength – like catching three hundred foxes and tying their tails together (Judges 15:4), or slaying a thousand warriors with the jawbone of a donkey (15:15). It’s pretty colorful stuff – not to mention grisly, at times – but this is a sort of Paul Bunyanesque tall tale, so I think we can forgive the storytellers a little poetic license. When Samson gets mad, he’s kind of like the Incredible Hulk (except for the green skin thing, which the Bible never mentions). It’s not gamma rays that make Samson so powerful; it’s the fact – as he reveals to his lover Delilah (a Philistine sympathizer) – that “a razor has never come upon my head” (16:17). Delilah gets out the razor while he’s sleeping, and that’s the end of ol’ Sam’s super-strength.

When Samson gets mad, he’s kind of like the Incredible Hulk (except for the green skin thing, which the Bible never mentions). It’s not gamma rays that make Samson so powerful; it’s the fact – as he reveals to his lover Delilah (a Philistine sympathizer) – that “a razor has never come upon my head” (16:17). Delilah gets out the razor while he’s sleeping, and that’s the end of ol’ Sam’s super-strength.At least for a while. As he’s languishing in prison, Samson’s hair starts to grow back. In the climactic final scene, he pulls down the stone pillars of the Philistines’ banqueting hall, killing more people in that one act than he’d killed in his entire life. He also sacrifices his own life, buried in the rubble.

It just goes to show how powerful a symbol hair is. For most of us, it’s part of our self-image, our sense of who we are. I suppose what bothers me most about losing it is the subconscious fear that my cancer is going to change me, on some fundamental level – that it will somehow take away my personhood. It won’t, of course – but, like many others who’ve got this disease, I’m going to have to work on seeing myself as a person with cancer, rather than a victim of it.

It just goes to show how powerful a symbol hair is. For most of us, it’s part of our self-image, our sense of who we are. I suppose what bothers me most about losing it is the subconscious fear that my cancer is going to change me, on some fundamental level – that it will somehow take away my personhood. It won’t, of course – but, like many others who’ve got this disease, I’m going to have to work on seeing myself as a person with cancer, rather than a victim of it.

Rachel Naomi Remen

Rachel Naomi Remen