Both funerals involved the familiar ritual of family and friends gathering at the funeral home, for what is blandly and euphemistically called “visiting hours.” In my more than 25 years of ordained ministry, I’ve been to more of these gatherings than I could possibly count. It goes with the territory, when you’re in ministry.

Both funerals involved the familiar ritual of family and friends gathering at the funeral home, for what is blandly and euphemistically called “visiting hours.” In my more than 25 years of ordained ministry, I’ve been to more of these gatherings than I could possibly count. It goes with the territory, when you’re in ministry.There’s not a lot that happens, during visiting hours (or so it would appear, to the untrained eye). After spending a few moments greeting the bereaved family and expressing words of sympathy, most guests simply sit or stand around, sharing small talk with neighbors. It’s one of the few occasions in life when all you have to do is show up.

Over the years, I’ve come to realize there’s a lot more going on during visiting hours. What the eye sees is but the tip of the iceberg.

There’s a new book called Social Intelligence: The New Science of Human Relationships, by Daniel Goleman, that’s been getting a lot of press. I haven’t read it, but from the reviews, it appears to have a lot to say about what goes on behind the scenes in many human interactions.

Based on psychological research, Goleman’s point is that a large portion of our emotional interactions are non-verbal, and take place on a subconscious level. In an October 10th essay in the New York Times, “Friends for Life: An Emerging Biology of Emotional Healing,” Goleman describes his findings:

“Research on the link between relationships and physical health has established that people with rich personal networks – who are married, have close family and friends, are active in social and religious groups – recover more quickly from disease and live longer. But now the emerging field of social neuroscience, the study of how people’s brains entrain as they interact, adds a missing piece to that data.

“Research on the link between relationships and physical health has established that people with rich personal networks – who are married, have close family and friends, are active in social and religious groups – recover more quickly from disease and live longer. But now the emerging field of social neuroscience, the study of how people’s brains entrain as they interact, adds a missing piece to that data. The most significant finding was the discovery of ‘mirror neurons,’ a widely dispersed class of brain cells that operate like neural WiFi. Mirror neurons track the emotional flow, movement and even intentions of the person we are with, and replicate this sensed state in our own brain by stirring in our brain the same areas active in the other person.”

Goleman reports that some researchers have used language like “the merging of two discrete physiologies into a connected circuit.” They think they’ve found evidence in brain chemistry to prove the existence of such a connection. While the physiology of this brain-to-brain link is highly speculative at this point, there does seem to be some circumstantial evidence that such a link exists: such as one study that asked women volunteers to submit to MRI imaging, while awaiting a mild electrical shock. When one of these experimental subjects waited alone, her anxiety level increased. When a stranger held her hand, her anxiety level was unchanged. Yet, when the woman’s husband held her hand, “she not only felt calm, but her brain circuitry quieted, revealing the biology of emotional rescue.”

No, there’s a lot going on during visiting hours in the funeral home – as people awkwardly mill around, seemingly doing nothing. They may not be consciously aware of it, but they’ve come there that day to plug into the power grid of spiritual and emotional support. By their mere presence in the room, they lend strength to their bereaved family, friends or neighbors.

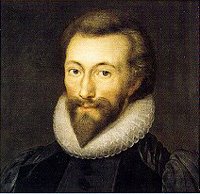

No, there’s a lot going on during visiting hours in the funeral home – as people awkwardly mill around, seemingly doing nothing. They may not be consciously aware of it, but they’ve come there that day to plug into the power grid of spiritual and emotional support. By their mere presence in the room, they lend strength to their bereaved family, friends or neighbors.Centuries ago, the Elizabethan preacher and poet John Donne penned these famous words, as he wondered, during a time of plague, whether the funeral bells from a nearby church might soon be tolling for him:

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were. Any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” ("Meditation XVII," from Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions)

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were. Any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” ("Meditation XVII," from Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions)One thing my cancer has taught me is the importance of these connections between people. We can be agents of each other’s healing.