This evening I attend a support-group meeting at the Cancer Concern Center. I’ve been continuing to attend these meetings whenever I can. I don’t have a lot to share, these days, by way of medical news, but there’s something I like about this diverse group of people, united by the common experience of cancer.

If there’s a prevailing demographic for this group, it would be forty- and fifty-something women with breast cancer. Yet, while the breast-cancer contingent – always the most vocal, in cancer circles – has a slight majority in this gathering, there are men who come as well, and people with other kinds of cancer. We haven’t all had the same sorts of treatments, but there are enough experiences we share, across the many different types of cancer, to provide common ground on which to stand.

The group spends extra time addressing the concerns of a newly-diagnosed woman, who is facing the prospect of chemotherapy. She’s clearly frightened by it, and as we listen to her tell her story, I recall how scared I was in the weeks leading up to my treatments. We reassure her that, while chemo is no picnic, it’s also something that need not be completely debilitating. There is much joy to be discovered in life, even in the midst of chemotherapy. Mental attitude is important, as is seeking out sources of support (such as this group).

I’ve heard it said that the most difficult time, in the life of a cancer survivor, is the time of diagnosis. It would be one thing if diagnosis were like other trips to the doctor, for less-serious ailments – “Here’s what’s wrong with you, and here’s a prescription that will make you better” – but it’s never that way. By its very nature, cancer diagnosis is complex. It’s a process. We start out hearing, “There’s a possibility you may have cancer,” and go on from there, through multiple tests and scans, until the day when the diagnosis is confirmed. Then, other tests and scans may follow, to determine exactly what type of cancer it is, and what sort of treatment is called for. In between each step in the process, there are frustrating periods of waiting – for lab results to come back, or for an opening to appear in a doctor’s apppointment-book. As we wait, we wonder:

Am I waiting too long? Will every week – every DAY – spent waiting set my recovery back? Should I make myself a nuisance in the doctor’s office, demanding the next possible appointment?

Then, there’s the vexing question of second opinions. Most experts agree that second opinions are a very good thing, when it comes to cancer treatment – good oncologists, in fact, value a team approach to diagnosis and treatment, and have no objection to waiting while the patient consults another physician. Yet, in those anxious days leading up to diagnosis, a second opinion can seem like just one more obstacle to getting on with it, to

getting free of the disease.

That sort of thinking is a big mistake. There are few cancer treatments that are so urgently required that a few weeks devoted to seeking a second opinion is medically harmful. (In those rare cases, we can trust our doctors to tell us so – and to explain why.) There’s absolutely nothing wrong with telling our doctor of our desire for a second opinion – treating it as a collaboration, rather than a challenge. Even if we end up with no change in the proposed treatment, we’ll be able to undertake that treatment with greater confidence and less second-guessing.

A change in perspective is necessary, when it comes to cancer. Cancer is not like many other medical conditions, that can easily be resolved with a prescription, or with some sort of surgery. Even when cancer

is treated surgically, there are years of tests and follow-ups afterwards, to make sure the surgeon “got it all.” No, for cancer survivors, it’s the moment of diagnosis that changes our lives – only it’s not a moment at all, it’s a season. Living through that season is one of the toughest things any of us do. We start out feeling isolated, and alone. We wonder who, out of all our friends, acquaintances, co-workers, can be trusted to bear the weight of our fearsome news. If we’re lucky, we find good people – family, friends, fellow church members, a dedicated cancer support group – who are up to the challenge of walking with us through it.

It’s a beautiful thing to watch the members of this particular support group close ranks around a new member – listening, helping, sharing strength. Why would anyone want to face an adversary like cancer alone?

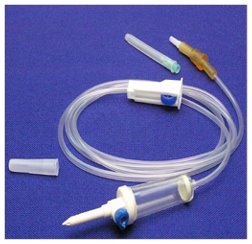

I haven’t thought much about my chemotherapy for some time, but suddenly it all comes back to me. Vanessa approaches me with a heavy-duty, medical paper towel, on which she’s got balanced a syringe, an L-shaped needle, a tube and some little paper packets. “Which side?” she asks.

I haven’t thought much about my chemotherapy for some time, but suddenly it all comes back to me. Vanessa approaches me with a heavy-duty, medical paper towel, on which she’s got balanced a syringe, an L-shaped needle, a tube and some little paper packets. “Which side?” she asks. Opening the paper packets, she removes some cotton swabs, pre-soaked with red-brown Betadine solution, and wipes them over the area of my chest, below the right collarbone, where the port hides just under the skin. “Deep breath,” she says. Obediently, I breathe in deeply, then feel the familiar prick of the needle. It hurts a little more than a blood-test – it’s a bigger needle – but not much. Like most people, I used to dread needle sticks, but now I hardly give them a thought. I’m a pro. Cancer treatment will do that to you. This is nothing – a mere dry run, compared to an actual chemo treatment.

Opening the paper packets, she removes some cotton swabs, pre-soaked with red-brown Betadine solution, and wipes them over the area of my chest, below the right collarbone, where the port hides just under the skin. “Deep breath,” she says. Obediently, I breathe in deeply, then feel the familiar prick of the needle. It hurts a little more than a blood-test – it’s a bigger needle – but not much. Like most people, I used to dread needle sticks, but now I hardly give them a thought. I’m a pro. Cancer treatment will do that to you. This is nothing – a mere dry run, compared to an actual chemo treatment. Taking up the syringe, attached to the needle by a plastic tube, Vanessa slowly presses the plunger. Instantly, I feel an odd, bubbling sensation in the back of my throat, accompanied by a peculiar plastic taste. That taste brings it all back, as though I were one of Pavlov’s dogs. I feel vaguely nauseated for a moment. It’s the prelude to chemotherapy – but, thankfully, there will be no chemotherapy for me today.

Taking up the syringe, attached to the needle by a plastic tube, Vanessa slowly presses the plunger. Instantly, I feel an odd, bubbling sensation in the back of my throat, accompanied by a peculiar plastic taste. That taste brings it all back, as though I were one of Pavlov’s dogs. I feel vaguely nauseated for a moment. It’s the prelude to chemotherapy – but, thankfully, there will be no chemotherapy for me today.