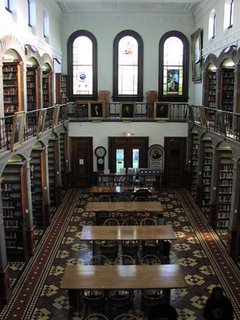

Last night, I was up at New Brunswick Theological Seminary, for my weekly teaching stint (I teach a course called “Presbyterian Studies,” for Presbyterian ministerial candidates enrolled in that Reformed Church in America seminary). During the chapel service, the worship leader invited the assembled faculty and students to offer sentence prayers – brief, spoken intercessions.

Last night, I was up at New Brunswick Theological Seminary, for my weekly teaching stint (I teach a course called “Presbyterian Studies,” for Presbyterian ministerial candidates enrolled in that Reformed Church in America seminary). During the chapel service, the worship leader invited the assembled faculty and students to offer sentence prayers – brief, spoken intercessions.Silently, I listened to the concerns raised by others. They were exactly the sort of items you’d expect to hear, in a seminary chapel service. There were general intercessions – for peace in the world, justice for the oppressed, safety for soldiers in Iraq, insight in academic study. There were also some specific prayer requests: first names of people, along with brief explanations of their circumstances. Someone had just lost a spouse, someone else was unemployed, still another person was hospitalized.

Then, someone offered prayer for “people who have cancer.” Suddenly, the service got very, very personal for me. I’d been letting the words of the prayers wash over me, with a kind of detached interest. When I heard those words, I found myself in a different place. I wasn’t just praying. I was being prayed for.

Then, someone offered prayer for “people who have cancer.” Suddenly, the service got very, very personal for me. I’d been letting the words of the prayers wash over me, with a kind of detached interest. When I heard those words, I found myself in a different place. I wasn’t just praying. I was being prayed for.The man who voiced this concern surely wasn’t thinking of me, in particular. I’m an adjunct professor – a visiting firefighter, who teaches his class, then goes home. That makes me a virtual stranger to most of the seminary community. Of those who do know me, only a few are aware of my recent medical history. The man who offered this prayer for cancer patients probably started out with someone altogether different in mind, and kindly extended his concern to embrace others.

I was touched, all the same. I smiled to myself, realizing that the people to my left and right probably had no idea they were praying for me, as they joined their thoughts to those of the speaker.

We have a wireless access point in our house, allowing various computers to log onto the Internet. Anyone who turns on a laptop, within the limited range of that antenna, can make use of the connection. Because the device includes a built-in hardware firewall, I haven’t felt the need to enable its password-protection feature. I figure that anyone who should happen to power on a laptop in a car outside our house is welcome to ramp onto the information superhighway, toll-free. If whole cities, like Philadelphia, are equipping their business districts with free, wireless Internet access, then why shouldn’t I offer a similar gift to the universe?

We have a wireless access point in our house, allowing various computers to log onto the Internet. Anyone who turns on a laptop, within the limited range of that antenna, can make use of the connection. Because the device includes a built-in hardware firewall, I haven’t felt the need to enable its password-protection feature. I figure that anyone who should happen to power on a laptop in a car outside our house is welcome to ramp onto the information superhighway, toll-free. If whole cities, like Philadelphia, are equipping their business districts with free, wireless Internet access, then why shouldn’t I offer a similar gift to the universe?I was on the receiving end of a similar kind of generosity last night, in the seminary chapel. That sentence prayer was like a wireless access point. I found myself in range, so I connected.

Reflecting on the experience of prayer, Roberta Bondi likens it to family ties:

“We often have a kind of notion, as part of this highfalutin’, noble picture of ourselves as pray-ers, that when we pray we need to be completely attentive and we need to be fully engaged and we need to be concentrating and we need to be focused. But the fact is, if prayer is our end of a relationship with God, that's not the way we are with the people we love a large portion of the time. We simply are in their presence. We're going about our lives at the same time in each other's presence, aware and sustained by each other, but not much more than that… However we are, however we think we ought to be in prayer, the fact is we just need to show up and do the best we can do. It's like being in a family.”

“We often have a kind of notion, as part of this highfalutin’, noble picture of ourselves as pray-ers, that when we pray we need to be completely attentive and we need to be fully engaged and we need to be concentrating and we need to be focused. But the fact is, if prayer is our end of a relationship with God, that's not the way we are with the people we love a large portion of the time. We simply are in their presence. We're going about our lives at the same time in each other's presence, aware and sustained by each other, but not much more than that… However we are, however we think we ought to be in prayer, the fact is we just need to show up and do the best we can do. It's like being in a family.”It just goes to show – when we are so bold as to offer up a prayer to God, we never know who may be in range.