This evening I preside at Madeline’s funeral. She’s the church member in her fifties who died in hospice care several weeks ago, after a long struggle with ovarian cancer. The family decided to wait a couple of weeks until I was through my most recent chemo treatment, so I could conduct her service.

This evening I preside at Madeline’s funeral. She’s the church member in her fifties who died in hospice care several weeks ago, after a long struggle with ovarian cancer. The family decided to wait a couple of weeks until I was through my most recent chemo treatment, so I could conduct her service.I remember when Madeline was first diagnosed. Her prognosis was not very encouraging, but she and her husband Dave stepped right up to the challenge, learned as much as they could about the disease and pursued aggressive treatment for as long as it seemed medically advisable to do so. I remember one night when they came into the Disciple Bible Study group I was teaching, and distributed educational materials about ovarian cancer to their fellow class members. They were on a mission that night: they wanted other women (and the men who love them) to know about the disease, and about the importance of early detection. It was just like Madeline – who combined deep caring for others with a no-nonsense, practical attitude – to do something like that.

Tonight I do feel well enough to conduct her service – but only just. A week after the most difficult of my chemo treatments so far, I don’t have a lot of stamina. It’s a good thing the funeral service is composed of a number of short segments. With Robin assisting me, I’m able to limit the time on my feet, and get through it without much difficulty.

Last week, when Dottie – my Presbyterian-minister colleague – stopped by to visit me during my chemo treatment, one of the pieces of advice she gave me was, “Don’t be a hero.” From her own experience as a cancer survivor – and perhaps knowing, also, that I’m the overly-conscientious type – she was encouraging me to take whatever time I need to get better, and let others handle my tasks at the church. I hear what she was saying, and I know I don’t absolutely need to be here tonight (Robin could very capably handle the service). Yet, in another sense, I do need to be here. What I need to do tonight is not something very many other people could do in my place. It’s a Cancer Underground sort of thing.

It’s hard to put into words, but I have a sense, tonight, that Madeline and I had a special connection because of our cancer. I choose to read these words from the letter to the Romans about suffering and endurance, because they somehow speak to our common experience:

“...we also boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us.” (Romans 5:3-5)

“...we also boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us.” (Romans 5:3-5)I haven’t figured out, in advance, exactly what to say about this passage, so I just wing it. I speak about sickness as a stern and demanding teacher. The lessons people like Madeline and me learn from our illness are not the sort that can be put into words. They have more to do with who we are becoming, as a result of the experience. The fact that Madeline is no longer a cancer survivor, while I still am, is incidental. Our faith assures us there is life after death, and that therefore this hope, born of endurance and character, carries us onward into the life to come.

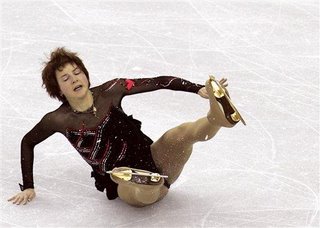

The image that comes to my mind, as I think later about what sort of thing cancer teaches, is that of an Olympic skater. These athletes put themselves through years of demanding training, in order that they may become the sort of people they know they are meant to be. There are falls and injuries along the way. Sometimes the falls happen in competition, and that is painful to behold – but they get up and skate on. Maybe the most important trait these athletes need, in order to become champions, is this very ability to get up, again and again, after they have fallen.

The image that comes to my mind, as I think later about what sort of thing cancer teaches, is that of an Olympic skater. These athletes put themselves through years of demanding training, in order that they may become the sort of people they know they are meant to be. There are falls and injuries along the way. Sometimes the falls happen in competition, and that is painful to behold – but they get up and skate on. Maybe the most important trait these athletes need, in order to become champions, is this very ability to get up, again and again, after they have fallen.One thing I find noteworthy about the Romans passage is that Paul does not seem to consider character to be a given. Most of us consider character to be the result of having come from a good family, having had the right upbringing, and so forth. But his is a more dynamic idea of character. It’s not anything we can take credit for. It’s what life makes of us, in the mysterious providence of God.

Back home after the service, Claire tells me my voice was not so strong as it usually is. She could see my physical weakness as I stood at the pulpit, and probably others could, too. Yet in another sense, I feel strong, stronger than I’ve ever been before. That’s all because of suffering, which produces endurance, character – and hope.