This morning I return a voice-mail message from Dr. Lerner that I discovered late last night. The message said he'd spoken with Dr. Portlock, and wanted to touch base with me prior to my trip to New York. His answering service tracks him down, and we speak a few minutes later.

Dr. Portlock, it seems, is especially keen to see my pathology slides. After reviewing the narrative report of the PET scan indicating the size of the mass in my abdomen, she wants to have her pathologist review the slides to make sure Dr. Lerner's diagnosis is correct. She wants to confirm that it is indeed the "matted mass of enlarged lymph nodes" Dr. Lerner has supposed it to be, and not a "bulky tumor." A bulky tumor, Dr. Lerner explains, would mean a more aggressive cancer. The way to determine the true identity of the abdominal mass is by carefully analyzing the microscope slides: if the tissue sample is composed of mostly small cells, he says, I do indeed have an indolent cancer. If there are other sorts of cells there, I could be in for a very different sort of ride.

After hanging up, I begin to worry a bit. Does Dr. Portlock, the famous lymphoma specialist, have some sort of inside track that leads her to suspect I may have a more serious condition? But wait, I say to myself. She hasn't seen all the data yet: she's just responding to the narrative report from the radiologist who read the PET scan. She hasn't even seen the PET scan films. They're still inside that big envelope sitting in the entry hall of our home, awaiting my trip to New York on Tuesday.

Dr. Portlock is simply doing what a good physician does, in preparing to issue a second opinion: she's taking everything back to the beginning, so she can look at all the evidence afresh. It's entirely possible, even likely, that her diagnosis will end up being the same as Dr. Lerner's.

I'm aware of how many of Dr. Lerner's conclusions are not based on his work alone. He's the oncologist coordinating my care, but he's depending heavily on the efforts of other professionals: the technicians who have administered my various tests and scans, as well as the other physicians – radiologists and pathologists – who have read the results. I've been hearing about the importance of a team approach in treating cancer, and it seems I've already got such a team. It's just that I've just never met most of them.

All these anonymous, white-coated professionals are interested in the "mass" inside me. What a nondescript word that is! Intentionally so, at this stage of the game. It may be a collection of swollen lymph nodes, it may be a tumor, or it may be something else altogether. The word "mass" is a sort of place-holder, a temporary term for everyone to use while the diagnosis and staging of my disease is still under way. We could just as well call it a "thing," a "lump," or even a "whatchamacallit" – though none of these terms offers the proper aura of scientific objectivity.

Suddenly my situation seems rather uncertain, still – nearly three months after that day when the ultrasound technician first remarked that something on the computer monitor didn't look right. These things take time, I have to remind myself. Indeed they do...

Since my December 2, 2005 Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma diagnosis, I've been on a slow-motion journey of survivorship. Chemo wiped out my aggressive disease in May, 2006, but an indolent variety is still lurking. I had my thyroid removed due to papillary thyroid cancer in 2011, and was diagnosed with recurrent thyroid cancer in 2017. Join me for a survivor's reflections on life, death, faith, politics, the Bible and everything else.

Saturday, December 31, 2005

December 30, 2005 - A Not-So-Long Wait, After All

Today I receive a surprise phone call from Dr. Portlock's receptionist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. The doctor – who has evidently conferred with Dr. Lerner by telephone – has had a cancellation in her schedule, and is wondering if I can come see her this Tuesday, January 3rd, instead of the 17th. Of course I agree. This appointment is the most important thing on my calendar, and I'm eager to see it happen sooner, rather than later.

Just yesterday I received, in a UPS courier envelope, the pre-appointment information packet from Dr. Portlock's office – along with a lengthy list of reports, scan films and pathology tissue samples that must be faxed or shipped to New York City. There was also a stern warning that, if all these requested reports and materials were not forthcoming, my appointment would be subject to cancellation. (They don't mess around, those Sloan-Kettering people.)

I spent most of yesterday afternoon authorizing the release of these records - as well as the Fedex shipping of the films and tissue samples - so as to arrive in time for the people at Sloan-Kettering to study them prior to the 17th. Now it appears that having these items in advance is not so important as all that: with the New Year's holiday weekend looming between now and my rescheduled appointment on Tuesday, I'm supposed to simply bring them with me. (Dr. Portlock has already received the narrative reports of these tests, which Dr. Lerner's office faxed to her yesterday; it's the actual films and slides I'll bring with me that day.)

After some quick phone calls to Ocean Medical Center, the Fedex shipment of radiology and nuclear medicine films is cancelled in the nick of time, and the Pathology Department locates and packs up the biopsy slides. I pick them up from the two different offices: several very large envelopes containing the radiology and nuclear medicine films, and a small, padded mailing envelope with the tissue samples inside.

How many fruits of my medical labors of the past month or two are concentrated in those parcels! And how difficult it would be, were they to be lost! Believe me, I will be keeping very, very close track of them.

It's an odd feeling to hold the padded envelope with the tissue samples inside. Those cells, removed from the mass in my abdomen and now pressed between glass microscope slides, were once a part of my body. Yet they are also the enemy: rebel cells that are now prisoners of war, facing interrogation. I hope they spill all their secrets.

Just yesterday I received, in a UPS courier envelope, the pre-appointment information packet from Dr. Portlock's office – along with a lengthy list of reports, scan films and pathology tissue samples that must be faxed or shipped to New York City. There was also a stern warning that, if all these requested reports and materials were not forthcoming, my appointment would be subject to cancellation. (They don't mess around, those Sloan-Kettering people.)

I spent most of yesterday afternoon authorizing the release of these records - as well as the Fedex shipping of the films and tissue samples - so as to arrive in time for the people at Sloan-Kettering to study them prior to the 17th. Now it appears that having these items in advance is not so important as all that: with the New Year's holiday weekend looming between now and my rescheduled appointment on Tuesday, I'm supposed to simply bring them with me. (Dr. Portlock has already received the narrative reports of these tests, which Dr. Lerner's office faxed to her yesterday; it's the actual films and slides I'll bring with me that day.)

After some quick phone calls to Ocean Medical Center, the Fedex shipment of radiology and nuclear medicine films is cancelled in the nick of time, and the Pathology Department locates and packs up the biopsy slides. I pick them up from the two different offices: several very large envelopes containing the radiology and nuclear medicine films, and a small, padded mailing envelope with the tissue samples inside.

How many fruits of my medical labors of the past month or two are concentrated in those parcels! And how difficult it would be, were they to be lost! Believe me, I will be keeping very, very close track of them.

It's an odd feeling to hold the padded envelope with the tissue samples inside. Those cells, removed from the mass in my abdomen and now pressed between glass microscope slides, were once a part of my body. Yet they are also the enemy: rebel cells that are now prisoners of war, facing interrogation. I hope they spill all their secrets.

Tuesday, December 27, 2005

December 27, 2005 - Cancer on My Mind

"You have a life-threatening disease that requires your IMMEDIATE attention. At this moment, there is NOTHING more important than stopping EVERYTHING else that you are doing in order to consider this." Those words come from a little book I’ve been reading, From This Moment On: A Guide for Those Recently Diagnosed with Cancer, by Arlene Cotter (Random House, 1999), p. 15.

"I’ve been aware that I’ve had cancer for every hour of every day of the eight years since my diagnosis." That’s the witness of NHL survivor Dr. Elizabeth Adler, in her book, Living With Lymphoma: A Patient’s Guide (Johns Hopkins, 2005), p. xii. (By the way, that’s the most helpful book I’ve found on lymphoma, generally. It was recommended to me by our friend Don. Written by a neurobiologist who contracted NHL herself, it’s got a powerful, one-two punch of personal testimony and very detailed medical information.)

Drop everything. Think of nothing but your disease. That’s the wake-up call for the newly diagnosed. Yet, if Dr. Adler’s experience is any guide, the diagnosis continues to be life-changing, even years later.

Perhaps Dr. Adler’s claim has a bit of hyperbole to it, or maybe I’m just different from her, but I wouldn’t say I’ve spent every waking hour thinking of the disease. This has been particularly true at Christmas, as there have been many joyful family gatherings to distract me – not to mention my pastoral responsibilities in planning for three services on Christmas Eve and one on Christmas Day. Yesterday I spent more than two hours in a movie theater, watching The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe with the family. I can’t say I thought about lymphoma a single time during that film, nor on the drive to and from the theater, either. It was wonderful, escapist entertainment. It would be accurate to say, though, that cancer has been at least a daily, often several-times-daily, reality in my thinking. It’s hard to get away from it.

Is this constant, almost obsessive thinking part of the disease process, or part of the healing process? There’s a whole spectrum of responses, I suppose: between obsessing over illness, on the one hand, and being appropriately engaged with the work of healing, on the other.

Everything I’ve always heard from cancer experts says the patient’s mental state is crucial. The most important thing may be not so much whether we’re thinking about our illness, but how.

"I’ve been aware that I’ve had cancer for every hour of every day of the eight years since my diagnosis." That’s the witness of NHL survivor Dr. Elizabeth Adler, in her book, Living With Lymphoma: A Patient’s Guide (Johns Hopkins, 2005), p. xii. (By the way, that’s the most helpful book I’ve found on lymphoma, generally. It was recommended to me by our friend Don. Written by a neurobiologist who contracted NHL herself, it’s got a powerful, one-two punch of personal testimony and very detailed medical information.)

Drop everything. Think of nothing but your disease. That’s the wake-up call for the newly diagnosed. Yet, if Dr. Adler’s experience is any guide, the diagnosis continues to be life-changing, even years later.

Perhaps Dr. Adler’s claim has a bit of hyperbole to it, or maybe I’m just different from her, but I wouldn’t say I’ve spent every waking hour thinking of the disease. This has been particularly true at Christmas, as there have been many joyful family gatherings to distract me – not to mention my pastoral responsibilities in planning for three services on Christmas Eve and one on Christmas Day. Yesterday I spent more than two hours in a movie theater, watching The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe with the family. I can’t say I thought about lymphoma a single time during that film, nor on the drive to and from the theater, either. It was wonderful, escapist entertainment. It would be accurate to say, though, that cancer has been at least a daily, often several-times-daily, reality in my thinking. It’s hard to get away from it.

Is this constant, almost obsessive thinking part of the disease process, or part of the healing process? There’s a whole spectrum of responses, I suppose: between obsessing over illness, on the one hand, and being appropriately engaged with the work of healing, on the other.

Everything I’ve always heard from cancer experts says the patient’s mental state is crucial. The most important thing may be not so much whether we’re thinking about our illness, but how.

Friday, December 23, 2005

December 23, 2005 - How Are You?

Christmas will soon be upon us. Time for some last-minute shopping.

I rummage through the bag of small items I've picked up earlier for Claire's Christmas stocking. Not enough, I say to myself, trying to visualize how many small items it will take to create the obligatory bulging look, that makes for a good stocking. And so I walk down to our seaside town's little main-street shopping district, and go in and out of a few of the shops, in search of a few more stocking-stuffers.

We've got more than our share of gift shops in this resort town, and – like most locals – I don't tend to go into them very often. But this is Christmas.

In one of the shops, the proprietor greets me by name. I recognize her right away. I performed her daughter's wedding several years ago. They're not a church-member family, and I probably haven't seen her more than once or twice since the wedding, but we always give each other a cordial greeting. She fills me in on how her daughter and son-in-law are doing, in far-off Hawaii. She has a two-year-old grandchild now, she tells me. I share her joy.

"And how are you doing?" she asks.

I pause for a moment. How do I answer? It's a question I've had to face nearly every day since my diagnosis, in casual contacts with friends and strangers alike. There was a time when I'd respond to such a question with some easy pleasantry, effortlessly greasing the wheels of social interaction. But now, life is just a bit more complicated.

Do I dump the whole load, telling her I've got cancer, and am facing major changes in my life? Or do I go for the casual, stealth approach: "I'm just fine, the kids are getting bigger, the church is doing well, I've got lymphoma – and isn't it a nice day today?" Or do I avoid the subject altogether?

This time, I opt for the third approach. I tell her I'm doing OK. Not fine, or great, or fabulous – just OK. Because I am. It's the truth, or close enough to it. I'm getting by. There are plenty of worries, but also a goodly number of joys – and I don't have to look too hard to find them, especially two days before Christmas.

I've resolved to be entirely truthful about my medical condition: no secrets. But that's not quite the same thing as "the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth." To ladle out a full, steaming portion of truth may be too much for some appetites.

"How are you?" is a question with a multitude of meanings. It all depends on the context. Standing behind a shopping cart in the supermarket.... Sitting in an overstuffed chair a across from a psychotherapist... Perched on the crinkly paper on the edge of a doctor's examining-table... Shaking hands with parishioners at the church door... Sinking back into the bed-pillows beside one's spouse, at the end of a long day. In each context, the question has a different meaning, and a different sort of answer is expected.

Would that we could always answer that question with total honesty and forthrightness! Although I expect that, if we did, it would not be long before we'd plunge to the ground like Icarus, the wax on our wings melted from a too-close encounter with blazing human emotion. Maybe in the coming reign of God, when the lion lies down with the lamb, and every tear will be wiped from every face. But not now. Not yet.

How am I? I'm OK. Because I am.

I rummage through the bag of small items I've picked up earlier for Claire's Christmas stocking. Not enough, I say to myself, trying to visualize how many small items it will take to create the obligatory bulging look, that makes for a good stocking. And so I walk down to our seaside town's little main-street shopping district, and go in and out of a few of the shops, in search of a few more stocking-stuffers.

We've got more than our share of gift shops in this resort town, and – like most locals – I don't tend to go into them very often. But this is Christmas.

In one of the shops, the proprietor greets me by name. I recognize her right away. I performed her daughter's wedding several years ago. They're not a church-member family, and I probably haven't seen her more than once or twice since the wedding, but we always give each other a cordial greeting. She fills me in on how her daughter and son-in-law are doing, in far-off Hawaii. She has a two-year-old grandchild now, she tells me. I share her joy.

"And how are you doing?" she asks.

I pause for a moment. How do I answer? It's a question I've had to face nearly every day since my diagnosis, in casual contacts with friends and strangers alike. There was a time when I'd respond to such a question with some easy pleasantry, effortlessly greasing the wheels of social interaction. But now, life is just a bit more complicated.

Do I dump the whole load, telling her I've got cancer, and am facing major changes in my life? Or do I go for the casual, stealth approach: "I'm just fine, the kids are getting bigger, the church is doing well, I've got lymphoma – and isn't it a nice day today?" Or do I avoid the subject altogether?

This time, I opt for the third approach. I tell her I'm doing OK. Not fine, or great, or fabulous – just OK. Because I am. It's the truth, or close enough to it. I'm getting by. There are plenty of worries, but also a goodly number of joys – and I don't have to look too hard to find them, especially two days before Christmas.

I've resolved to be entirely truthful about my medical condition: no secrets. But that's not quite the same thing as "the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth." To ladle out a full, steaming portion of truth may be too much for some appetites.

"How are you?" is a question with a multitude of meanings. It all depends on the context. Standing behind a shopping cart in the supermarket.... Sitting in an overstuffed chair a across from a psychotherapist... Perched on the crinkly paper on the edge of a doctor's examining-table... Shaking hands with parishioners at the church door... Sinking back into the bed-pillows beside one's spouse, at the end of a long day. In each context, the question has a different meaning, and a different sort of answer is expected.

Would that we could always answer that question with total honesty and forthrightness! Although I expect that, if we did, it would not be long before we'd plunge to the ground like Icarus, the wax on our wings melted from a too-close encounter with blazing human emotion. Maybe in the coming reign of God, when the lion lies down with the lamb, and every tear will be wiped from every face. But not now. Not yet.

How am I? I'm OK. Because I am.

December 22, 2005 - A Gift of Poetry

Today, out of the blue, I receive an e-mail from a friend I haven’t heard from for some time. Bob retired as Monmouth Presbytery’s executive presbyter several years ago, and has been living in Nova Scotia. He heard of my diagnosis, and decided to send some encouraging words.

Bob’s encouragement means a lot, because - as I’ve just learned - he has had a successful battle with cancer himself.

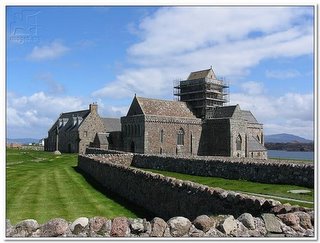

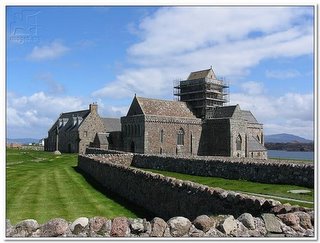

One thing Bob and I have in common is that we are both Associate Members of the Iona Community in Scotland. Here’s part of the e-mail he sent:

One thing Bob and I have in common is that we are both Associate Members of the Iona Community in Scotland. Here’s part of the e-mail he sent:

"As you have indicated, the lymphoma is in a deep, difficult place to reach - witness the (painless?) biopsy (which gave some good news). I read and re-read this prayer-poem by Maggie Wallis in the October 2005 issue of Iona Community’s Coracle. I claim that there is something else going on inside of you:

You inhabit my empty space

I watch the geese fly to you

The wind seek you endlessly

And in there

Somewhere beneath my rib cage

Is a spot I cannot touch

That aches

With the breadth and depth

Of Eternity

And that

I know is

You

All I know is that God is with us to bless and to heal. And I know God is with you NOW more than ever."

I couldn’t have said it better! Thanks, Bob.

Bob’s encouragement means a lot, because - as I’ve just learned - he has had a successful battle with cancer himself.

One thing Bob and I have in common is that we are both Associate Members of the Iona Community in Scotland. Here’s part of the e-mail he sent:

One thing Bob and I have in common is that we are both Associate Members of the Iona Community in Scotland. Here’s part of the e-mail he sent:"As you have indicated, the lymphoma is in a deep, difficult place to reach - witness the (painless?) biopsy (which gave some good news). I read and re-read this prayer-poem by Maggie Wallis in the October 2005 issue of Iona Community’s Coracle. I claim that there is something else going on inside of you:

You inhabit my empty space

I watch the geese fly to you

The wind seek you endlessly

And in there

Somewhere beneath my rib cage

Is a spot I cannot touch

That aches

With the breadth and depth

Of Eternity

And that

I know is

You

All I know is that God is with us to bless and to heal. And I know God is with you NOW more than ever."

I couldn’t have said it better! Thanks, Bob.

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

December 21, 2005 - When Negative is Positive

I’ve long been aware, through the course of my hospital visits as a pastor, that negative is usually positive – at least in the world of medical tests. A test that comes back negative means that the bad thing the doctors have been fearing they might find is not, in fact, there.

Such is my experience today. In the afternoon, I discover a voice mail message from Dr. Lerner’s office, asking me to please call to receive some test results. When I call back, I learn that my bone-marrow biopsy has come back negative: there’s no sign of malignancy there.

Good news, indeed! It means the cancer cells are restricted to the large mass in my abdomen and several nearby areas, and have not yet made the jump into the bone marrow (where blood cells are made). I’m still awaiting the doctor’s final assessment as to the formal staging of the disease – although he did predict, earlier, that if the bone marrow were not involved, I would likely be at stage 2. (Dr. Lerner did caution that, in follicular lymphomas like mine, the staging is not as important as the FLIPI score – which takes into account not only staging, but also several other factors that predict the success of treatment.)

Now I enter an extended waiting mode. My January 17th appointment with Dr. Portlock at Sloan-Kettering is almost a month away. My next appointment with Dr. Lerner is not until January 27th (timed to follow the assessment at Sloan-Kettering). My desire for a second opinion will end up pushing back the start of treatment by a month or more.

While a month’s delay may seem worrisome, everything I’ve learned about indolent lymphomas suggests that taking our time at this point in the process is not that big a deal. In fact, there are some very good reasons for doing so. Perhaps the most important decision related to my recovery is that of which treatment regimen to start with. Of all the decisions that must be made, this is the one to be sure to get right.

This will be a different sort of Christmas for me, and for our family. We will be more aware of the presence of darkness, of the ominous threat that has entered our lives. Yet why should we be surprised by this? Not even the first Christmas was without darkness. In the biblical story, the beatific vision of the holy child in the manger is countered by the horrors of King Herod’s jealous pursuit, and the tragic massacre of the innocents. This human life of ours is always a mix of triumph and tragedy. We take comfort where we can, remembering that "the people who walked in darkness have seen a great light" (Isaiah 9:2). Like the magi of old, we are all seekers of light.

Such is my experience today. In the afternoon, I discover a voice mail message from Dr. Lerner’s office, asking me to please call to receive some test results. When I call back, I learn that my bone-marrow biopsy has come back negative: there’s no sign of malignancy there.

Good news, indeed! It means the cancer cells are restricted to the large mass in my abdomen and several nearby areas, and have not yet made the jump into the bone marrow (where blood cells are made). I’m still awaiting the doctor’s final assessment as to the formal staging of the disease – although he did predict, earlier, that if the bone marrow were not involved, I would likely be at stage 2. (Dr. Lerner did caution that, in follicular lymphomas like mine, the staging is not as important as the FLIPI score – which takes into account not only staging, but also several other factors that predict the success of treatment.)

Now I enter an extended waiting mode. My January 17th appointment with Dr. Portlock at Sloan-Kettering is almost a month away. My next appointment with Dr. Lerner is not until January 27th (timed to follow the assessment at Sloan-Kettering). My desire for a second opinion will end up pushing back the start of treatment by a month or more.

While a month’s delay may seem worrisome, everything I’ve learned about indolent lymphomas suggests that taking our time at this point in the process is not that big a deal. In fact, there are some very good reasons for doing so. Perhaps the most important decision related to my recovery is that of which treatment regimen to start with. Of all the decisions that must be made, this is the one to be sure to get right.

This will be a different sort of Christmas for me, and for our family. We will be more aware of the presence of darkness, of the ominous threat that has entered our lives. Yet why should we be surprised by this? Not even the first Christmas was without darkness. In the biblical story, the beatific vision of the holy child in the manger is countered by the horrors of King Herod’s jealous pursuit, and the tragic massacre of the innocents. This human life of ours is always a mix of triumph and tragedy. We take comfort where we can, remembering that "the people who walked in darkness have seen a great light" (Isaiah 9:2). Like the magi of old, we are all seekers of light.

Tuesday, December 20, 2005

December 20, 2005 - In the Sloan-Kettering Book of Life

After several weeks of persistent efforts, I've finally succeeded in getting my name onto the calendar at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. On January 17th, I will meet with Dr. Carol Portlock, the lymphoma specialist whose name Dr. Lerner recognized when I told him about her.

It seems Dr. Portlock's office staff knows of Dr. Lerner as well. The receptionist recognized his name when I mentioned it to her. I consider that a good sign. My hope is that the two of them can collaborate on coordinating my care, and that whatever treatment regimen I may ultimately undergo can be administered in Dr. Lerner's office near our home. (I'm prepared to commute the 2+ hours to New York for chemotherapy if absolutely necessary, but I'd prefer not to – I've heard enough stories about chemo patients driving home with a nausea bucket on their knees, and would rather that drive be as short as possible.)

I've been feeling more fatigue than usual the last couple of days. I'm noticing that I'm sleeping for shorter periods of time at night, and awaking feeling more tired than usual. I've never been much of a one for midday naps – my experience has been that, even if I'm feeling tired, the best I can do is shut my eyes and doze a little, and I don't end up feeling very rested. (I can't remember much about my nursery school days, but I'd be willing to guess I was one of those kids who wiggled and squirmed through naptime!)

Is the fatigue a symptom of the lymphoma? Or is it more of a psychological response to the stress of this experience? It's hard to say, although the feelings of fatigue are unmistakable. And it feels different, somehow, from the sort of tiredness I feel when I've simply stayed up too late at night and arisen too early in the morning. My pesky internal clock seems to be getting me up at about 7:00 a.m., regardless of how tired I feel – so sleeping in doesn't seem to be an option.

Giving myself permission to stop and take a midday nap is not easy for me. My personality is closer to the "workaholic" than to the "laid-back" end of the scale. But this is probably a skill I'm going to need to learn...

It seems Dr. Portlock's office staff knows of Dr. Lerner as well. The receptionist recognized his name when I mentioned it to her. I consider that a good sign. My hope is that the two of them can collaborate on coordinating my care, and that whatever treatment regimen I may ultimately undergo can be administered in Dr. Lerner's office near our home. (I'm prepared to commute the 2+ hours to New York for chemotherapy if absolutely necessary, but I'd prefer not to – I've heard enough stories about chemo patients driving home with a nausea bucket on their knees, and would rather that drive be as short as possible.)

I've been feeling more fatigue than usual the last couple of days. I'm noticing that I'm sleeping for shorter periods of time at night, and awaking feeling more tired than usual. I've never been much of a one for midday naps – my experience has been that, even if I'm feeling tired, the best I can do is shut my eyes and doze a little, and I don't end up feeling very rested. (I can't remember much about my nursery school days, but I'd be willing to guess I was one of those kids who wiggled and squirmed through naptime!)

Is the fatigue a symptom of the lymphoma? Or is it more of a psychological response to the stress of this experience? It's hard to say, although the feelings of fatigue are unmistakable. And it feels different, somehow, from the sort of tiredness I feel when I've simply stayed up too late at night and arisen too early in the morning. My pesky internal clock seems to be getting me up at about 7:00 a.m., regardless of how tired I feel – so sleeping in doesn't seem to be an option.

Giving myself permission to stop and take a midday nap is not easy for me. My personality is closer to the "workaholic" than to the "laid-back" end of the scale. But this is probably a skill I'm going to need to learn...

Saturday, December 17, 2005

December 17, 2005 - A Passage to India

The internet is a strange and wonderful thing. I've been getting many warm, supportive comments from church friends and family who have been reading things I've written here, but one of the most remarkable is from a new friend who lives halfway around the world. Tarun Jacob is a medical doctor from India, who happened to run across my blog while doing some kind of web search. He sent me an e-mail, and we've been corresponding.

Tarun also happens to have non-Hodgkin lymphoma. He's currently receiving chemotherapy, and has a wonderful, upbeat attitude towards the whole experience. But he and I have more in common than that. First, he too has a blog, which he's been using to record his experiences; you can visit his blog by clicking here. (You really ought to check it out - he's got way more cool pictures on his blog than I do!) Second, he's a Christian. And third (along with his parents and his wife, who are also physicians), he's associated with the Christian Medical College in Vellore, India, which began as a Presbyterian medical mission and still has strong ties with the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). Small world!

I've written in earlier posts about what I call the Cancer Underground - that invisible network of support that has immediately reached out and enfolded me in love and caring. Well, it seems the Cancer Underground has a very long reach indeed. Amazing!

Or maybe it's not so amazing... because, I hasten to remind myself, God is at work in all of this. Who else could reach all the way to India, to arrange for a Christian brother and fellow NHL survivor to contact me and share his faith and concern?

Like I said... strange and wonderful!

Tarun also happens to have non-Hodgkin lymphoma. He's currently receiving chemotherapy, and has a wonderful, upbeat attitude towards the whole experience. But he and I have more in common than that. First, he too has a blog, which he's been using to record his experiences; you can visit his blog by clicking here. (You really ought to check it out - he's got way more cool pictures on his blog than I do!) Second, he's a Christian. And third (along with his parents and his wife, who are also physicians), he's associated with the Christian Medical College in Vellore, India, which began as a Presbyterian medical mission and still has strong ties with the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). Small world!

I've written in earlier posts about what I call the Cancer Underground - that invisible network of support that has immediately reached out and enfolded me in love and caring. Well, it seems the Cancer Underground has a very long reach indeed. Amazing!

Or maybe it's not so amazing... because, I hasten to remind myself, God is at work in all of this. Who else could reach all the way to India, to arrange for a Christian brother and fellow NHL survivor to contact me and share his faith and concern?

Like I said... strange and wonderful!

Thursday, December 15, 2005

December 15, 2005 - The View From the Bone-Marrow Biopsy Table

This afternoon I am lying on my left side on an examining table in Dr. Lerner’s office, while he goes about the business of conducting a bone-marrow biopsy. Earlier he has admitted that this procedure may be "a bit uncomfortable" – which I took to be a tacit admission that it’s painful.

The nurse who weighs me and leads me back to the bloodletting room seems unusually solicitous, asking very specifically how I’m feeling. I tell her I’m a bit nervous – what does she expect? – and she goes out of her way to assure me that although the procedure is uncomfortable, I will feel no pain. Not with Dr. Lerner doing it, she says, proudly.

It turns out she’s right. He’s really good. A slight prick of the needle as the doctor numbs the skin of my lower back, down near the right hip, a wait of several minutes while the anesthetic takes effect, and he goes about his work. Breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth, and do it slowly, the nurse says. She repeats the mantra several times over the next few minutes, as they’re getting me into position. Even the doctor says it at one point. I’m reminded of the Lamaze breathing exercises Claire and I practiced years ago, before the birth of our children. I find this breathing instruction both calming and anxiety-producing: calming, because that’s what that sort of breathing does; and anxiety-producing, because they’re making such a point of insisting on it.

The nurse takes her position in front of me and presses down hard on my right hip with all her weight, to immobilize me. (Not a good sign, I think to myself.) The doctor inserts his needle into the bone to draw out some fluid, telling me exactly what he’s doing at each stage of the process. I feel pressure as it goes in, but it’s not painful. Then he does the same thing with some kind of handheld device that punches into the bone as he twists it like a corkscrew. (I didn’t actually get a look at the thing, but I expect it’s one of these lovely implements: click here.) Again, I feel pressure – much greater this time – but I wouldn’t describe the sensation as pain. There’s a sort of intense throbbing, down near my tailbone, that comes and goes. Dr. Lerner remarks that my bones are stronger than those of most people for whom he does this procedure: "It’s a good thing I ate my Wheaties this morning," he quips, as he leans in harder. He says he’s used to doing bone-marrow biopsies on people much older than me, whose bones are thinner.

It’s all over in about two minutes. Dr. Lerner bandages the wound, and the nurse tells me I must lie on my back for a considerable time, with my feet flat on the table and my knees drawn up. They call Claire into the room, and we check in with Dr. Lerner on how my case is progressing.

From my awkward position on the table, I tell Dr. Lerner that, as of today, I’ve finally been assigned a doctor at Memorial Sloan-Kettering. Her name is Dr. Carol Portlock. Dr. Portlock’s office is supposed to call me very soon, to arrange an appointment. Dr. Lerner recognizes her name immediately. "She’s famous in the world of lymphoma specialists," he tells me. I tell him I’d figured as much, having Googled her name this afternoon, and discovered all manner of references to journal articles and medical-conference speeches.

I ask Dr. Lerner about my mugascan results. They came back fine, he says: no heart issues that could interfere with chemotherapy.

I ask him about staging – which rating of severity he thinks he will give to my case if the biopsy comes back positive, and which if it comes back negative (the word "staging" refers to how extensively the cancer is spread throughout the body). Dr. Lerner tells me I should not be surprised if the test comes back showing some bone marrow involvement, as this is fairly common with my type of lymphoma. Should that happen, I will be at stage 4 (the highest stage). Should the biopsy come back clean, I’ll probably be at stage 2. But don’t put too much stock in the staging numbers, he warns – because with indolent lymphomas like mine, the far more significant figure is something called the FLIPI scale ("Follicular Lymphoma Prognostic Index"). In addition to traditional staging, this scale takes into account such factors as the patient’s age, hemoglobin level, number of affected lymph nodes throughout the body, and serum LDH level (a blood-chemistry reading). The FLIPI scale is a better predictor of how patients will actually respond to treatment.

We drive back home, and I spend the next few hours sitting and resting: first in front of the television, then in the living room, as the family hangs ornaments on the Christmas tree. My role in this year’s holiday tradition is purely supervisory. When we’re finished admiring the tree and I start walking up the stairs, I experience the worst pain of the day: about the level of a really nasty pulled muscle, all up and down my right leg. I’m OK as long as I don’t walk around, so I decide to sit down at the computer and write this journal entry. It feels good to be doing something productive, after being on the receiving end of treatment all afternoon. And that, good reader, is why I’m going through this crazy exercise of keeping a cancer journal. Studying and writing about this disease and my reactions to it feels like something positive I can do. It’s a small remedy for the lack of control I’m feeling.

The nurse who weighs me and leads me back to the bloodletting room seems unusually solicitous, asking very specifically how I’m feeling. I tell her I’m a bit nervous – what does she expect? – and she goes out of her way to assure me that although the procedure is uncomfortable, I will feel no pain. Not with Dr. Lerner doing it, she says, proudly.

It turns out she’s right. He’s really good. A slight prick of the needle as the doctor numbs the skin of my lower back, down near the right hip, a wait of several minutes while the anesthetic takes effect, and he goes about his work. Breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth, and do it slowly, the nurse says. She repeats the mantra several times over the next few minutes, as they’re getting me into position. Even the doctor says it at one point. I’m reminded of the Lamaze breathing exercises Claire and I practiced years ago, before the birth of our children. I find this breathing instruction both calming and anxiety-producing: calming, because that’s what that sort of breathing does; and anxiety-producing, because they’re making such a point of insisting on it.

The nurse takes her position in front of me and presses down hard on my right hip with all her weight, to immobilize me. (Not a good sign, I think to myself.) The doctor inserts his needle into the bone to draw out some fluid, telling me exactly what he’s doing at each stage of the process. I feel pressure as it goes in, but it’s not painful. Then he does the same thing with some kind of handheld device that punches into the bone as he twists it like a corkscrew. (I didn’t actually get a look at the thing, but I expect it’s one of these lovely implements: click here.) Again, I feel pressure – much greater this time – but I wouldn’t describe the sensation as pain. There’s a sort of intense throbbing, down near my tailbone, that comes and goes. Dr. Lerner remarks that my bones are stronger than those of most people for whom he does this procedure: "It’s a good thing I ate my Wheaties this morning," he quips, as he leans in harder. He says he’s used to doing bone-marrow biopsies on people much older than me, whose bones are thinner.

It’s all over in about two minutes. Dr. Lerner bandages the wound, and the nurse tells me I must lie on my back for a considerable time, with my feet flat on the table and my knees drawn up. They call Claire into the room, and we check in with Dr. Lerner on how my case is progressing.

From my awkward position on the table, I tell Dr. Lerner that, as of today, I’ve finally been assigned a doctor at Memorial Sloan-Kettering. Her name is Dr. Carol Portlock. Dr. Portlock’s office is supposed to call me very soon, to arrange an appointment. Dr. Lerner recognizes her name immediately. "She’s famous in the world of lymphoma specialists," he tells me. I tell him I’d figured as much, having Googled her name this afternoon, and discovered all manner of references to journal articles and medical-conference speeches.

I ask Dr. Lerner about my mugascan results. They came back fine, he says: no heart issues that could interfere with chemotherapy.

I ask him about staging – which rating of severity he thinks he will give to my case if the biopsy comes back positive, and which if it comes back negative (the word "staging" refers to how extensively the cancer is spread throughout the body). Dr. Lerner tells me I should not be surprised if the test comes back showing some bone marrow involvement, as this is fairly common with my type of lymphoma. Should that happen, I will be at stage 4 (the highest stage). Should the biopsy come back clean, I’ll probably be at stage 2. But don’t put too much stock in the staging numbers, he warns – because with indolent lymphomas like mine, the far more significant figure is something called the FLIPI scale ("Follicular Lymphoma Prognostic Index"). In addition to traditional staging, this scale takes into account such factors as the patient’s age, hemoglobin level, number of affected lymph nodes throughout the body, and serum LDH level (a blood-chemistry reading). The FLIPI scale is a better predictor of how patients will actually respond to treatment.

We drive back home, and I spend the next few hours sitting and resting: first in front of the television, then in the living room, as the family hangs ornaments on the Christmas tree. My role in this year’s holiday tradition is purely supervisory. When we’re finished admiring the tree and I start walking up the stairs, I experience the worst pain of the day: about the level of a really nasty pulled muscle, all up and down my right leg. I’m OK as long as I don’t walk around, so I decide to sit down at the computer and write this journal entry. It feels good to be doing something productive, after being on the receiving end of treatment all afternoon. And that, good reader, is why I’m going through this crazy exercise of keeping a cancer journal. Studying and writing about this disease and my reactions to it feels like something positive I can do. It’s a small remedy for the lack of control I’m feeling.

December 14, 2005 - The Eye of the Needle

I have had several phone conversations in recent days with Dr. Lerner’s office staff and with staff from Sloan-Kettering, trying to resolve the question of the biopsy results, and whether I will have to undergo the procedure a second time in order to meet Sloan-Kettering’s admission requirements. Slowly the source of the problem has emerged. It appears to have been a simple misunderstanding. Something written on the narrative lab report that was faxed to Sloan-Kettering led their Lymphoma Department to think I had had only a fine-needle aspiration biopsy. I have since learned that what I actually had was both a fine-needle aspiration and a core-needle biopsy (using the largest possible needle, in fact). The Sloan-Kettering people have told Dr. Lerner’s staff that a core-needle biopsy probably did produce a large enough tissue sample for their purposes. They will know for sure when they actually receive the set of slides that was prepared by the pathologist, but they don’t anticipate a problem.

What a difference a small record-keeping glitch can make! I’m feeling relieved that a second biopsy does not appear to be in my immediate future.

Tomorrow afternoon is my bone-marrow biopsy, that procedure Dr. Lerner frankly described as "uncomfortable." I’m not looking forward to it. I’ll have to try to practice that discipline Cindy talked about, of "going to a different place."

What a difference a small record-keeping glitch can make! I’m feeling relieved that a second biopsy does not appear to be in my immediate future.

Tomorrow afternoon is my bone-marrow biopsy, that procedure Dr. Lerner frankly described as "uncomfortable." I’m not looking forward to it. I’ll have to try to practice that discipline Cindy talked about, of "going to a different place."

Monday, December 12, 2005

December 11, 2005 - Seeing You Seeing Me

Today is Sunday, a week since my announcement to the congregation. Our Chancel Choir has presented a wonderful Christmas program. I've written a narration to introduce each of the suite of familiar carols the choir is singing, and my contribution is well-received. I'm relieved that there's no need, today, to say a thing about my medical situation in worship. It's good to have a normal Sunday.

I’m aware, of course, that my health is on many church members’ minds. I wonder, now – as the people look at their pastor, do they see a person who is less than whole? If so, what difference does that make?

As I'm greeting at the door afterwards, many people bring the subject up themselves, asking how I'm feeling. It's gratifying to know how much they care. I reply that I'm feeling fine and have no symptoms. A few people who have heard the news but weren't here the previous Sunday express their concern.

I have a moment, after the greeting at the door is over, to speak with Tom and Karen, who linger at the church door. Tom has recently retired as a school administrator, and has moved into private practice as a psychological therapist. Karen is a teacher. In the past year, Karen has completed a grueling round of surgery and chemotherapy at Sloan-Kettering for breast cancer. I'm aware that one factor in Tom's decision to retire early was the experience of walking with a loved one through cancer treatment. It caused him to re-think his priorities.

Karen is looking strong and healthy. Her hair has grown back. She and Tom speak very positively about Sloan-Kettering. They tell how, in the waiting rooms, they met people who had traveled there from all over the country. With a world-class facility like that just two hours away, they reason, why go anywhere else?

It's comforting to talk with Karen and Tom. They are examples of the saying, "What does not kill me makes me stronger." The Cancer Underground strikes again.

I’m aware, of course, that my health is on many church members’ minds. I wonder, now – as the people look at their pastor, do they see a person who is less than whole? If so, what difference does that make?

As I'm greeting at the door afterwards, many people bring the subject up themselves, asking how I'm feeling. It's gratifying to know how much they care. I reply that I'm feeling fine and have no symptoms. A few people who have heard the news but weren't here the previous Sunday express their concern.

I have a moment, after the greeting at the door is over, to speak with Tom and Karen, who linger at the church door. Tom has recently retired as a school administrator, and has moved into private practice as a psychological therapist. Karen is a teacher. In the past year, Karen has completed a grueling round of surgery and chemotherapy at Sloan-Kettering for breast cancer. I'm aware that one factor in Tom's decision to retire early was the experience of walking with a loved one through cancer treatment. It caused him to re-think his priorities.

Karen is looking strong and healthy. Her hair has grown back. She and Tom speak very positively about Sloan-Kettering. They tell how, in the waiting rooms, they met people who had traveled there from all over the country. With a world-class facility like that just two hours away, they reason, why go anywhere else?

It's comforting to talk with Karen and Tom. They are examples of the saying, "What does not kill me makes me stronger." The Cancer Underground strikes again.

December 9, 2005 - Dueling Oncologists?

My first experience with administrative red tape, today, in this whole process. Certainly it will not be my last. I received a call from the admissions people at Sloan-Kettering, saying they have received copies of the test results faxed by Dr. Lerner’s office, but that these are not enough. Sloan-Kettering, it seems, will not even put me on their calendar until I can present the results of an incisional biopsy. (My previous biopsy was a fine-needle aspiration, which yields only a small quantity of tissue for pathological analysis.) An incisional biopsy is more of a surgical procedure, in which a small piece of the tumor is cut out, rather than having some liquid or semi-liquid matter sucked out through a needle.

I am sitting in a waiting area at Ocean Medical Center waiting for my mugascan. Several messages and missed connections later, I have Dr. Lerner on my cell phone. He tells me that, in his opinion, an abdominal surgical procedure is probably unnecessary, because the fine-needle biopsy has already yielded a firm diagnosis. He suggests that a core-needle biopsy, while not strictly speaking an incisional procedure, could perhaps yield enough tissue. (In a core-needle biopsy, tiny instruments are extended down the middle of a hollow needle, so small pieces of tissue may be snipped out and removed.) This could be done in the same interventional radiology suite at Ocean Medical Center where I had my fine-needle biopsy, with the same quick recovery to be expected. Of course, had we known I would be contacting Sloan-Kettering and what their requirements are, Dr. Lerner could have ordered that sort of biopsy in the first place, saving me the need to go through a second surgical procedure. But we didn’t know that; the subject of a second opinion didn’t even come up until after the diagnosis.

Dr. Lerner explains that Sloan-Kettering, being a research-oriented institution, probably has routine procedures that require a larger number of pathology slides. I wonder if there is perhaps a misunderstanding, on the part of the Sloan-Kettering people, about the location of my tumor. Many NHL patients, like Cindy, have swollen lymph nodes in easily-accessible places, just under the skin. These lumps are, for them, the first noticeable signs of the disease. My diagnosis is a bit more unusual. My tumor was detected accidentally, through an ultrasound. It’s not so easily accessible, being buried deep in my abdomen.

Back on the phone to Sloan-Kettering. The woman on the other end of the line explains that this is what "the nurse" says is needed. She has talked to him again and confirmed that, yes, this is standard policy. She offers to talk to a doctor on my behalf, but few are around the office on this particular Friday, which is the day of a major medical conference. She offers to phone me back on Monday.

I wonder at a system that gives a nurse the power to overrule an M.D. Yet maybe that’s not so surprising, in the specialized world of cancer hospitals. I’ve heard about certain oncology nurses having very deep knowledge, more than many doctors, about the narrow slice of medical knowledge that is their specialty. I silently wish Dr. Lerner could somehow speak directly with a Sloan-Kettering physician about this, and spare me the role of being the communications conduit. Yet, in fairness to him, it’s my second opinion, not his. I’ve got to do the legwork myself.

I suppose this is what the literature means when it says patients must be their own advocates. I'm learning fast about how this game is played. But it's no game. It's my life.

I am sitting in a waiting area at Ocean Medical Center waiting for my mugascan. Several messages and missed connections later, I have Dr. Lerner on my cell phone. He tells me that, in his opinion, an abdominal surgical procedure is probably unnecessary, because the fine-needle biopsy has already yielded a firm diagnosis. He suggests that a core-needle biopsy, while not strictly speaking an incisional procedure, could perhaps yield enough tissue. (In a core-needle biopsy, tiny instruments are extended down the middle of a hollow needle, so small pieces of tissue may be snipped out and removed.) This could be done in the same interventional radiology suite at Ocean Medical Center where I had my fine-needle biopsy, with the same quick recovery to be expected. Of course, had we known I would be contacting Sloan-Kettering and what their requirements are, Dr. Lerner could have ordered that sort of biopsy in the first place, saving me the need to go through a second surgical procedure. But we didn’t know that; the subject of a second opinion didn’t even come up until after the diagnosis.

Dr. Lerner explains that Sloan-Kettering, being a research-oriented institution, probably has routine procedures that require a larger number of pathology slides. I wonder if there is perhaps a misunderstanding, on the part of the Sloan-Kettering people, about the location of my tumor. Many NHL patients, like Cindy, have swollen lymph nodes in easily-accessible places, just under the skin. These lumps are, for them, the first noticeable signs of the disease. My diagnosis is a bit more unusual. My tumor was detected accidentally, through an ultrasound. It’s not so easily accessible, being buried deep in my abdomen.

Back on the phone to Sloan-Kettering. The woman on the other end of the line explains that this is what "the nurse" says is needed. She has talked to him again and confirmed that, yes, this is standard policy. She offers to talk to a doctor on my behalf, but few are around the office on this particular Friday, which is the day of a major medical conference. She offers to phone me back on Monday.

I wonder at a system that gives a nurse the power to overrule an M.D. Yet maybe that’s not so surprising, in the specialized world of cancer hospitals. I’ve heard about certain oncology nurses having very deep knowledge, more than many doctors, about the narrow slice of medical knowledge that is their specialty. I silently wish Dr. Lerner could somehow speak directly with a Sloan-Kettering physician about this, and spare me the role of being the communications conduit. Yet, in fairness to him, it’s my second opinion, not his. I’ve got to do the legwork myself.

I suppose this is what the literature means when it says patients must be their own advocates. I'm learning fast about how this game is played. But it's no game. It's my life.

December 8, 2005 - A Different Place

Another rendezvous today with a member of the Cancer Underground. Steve, pastor of a nearby Presbyterian Church, had phoned me to suggest that Claire and I meet with him and his wife Cindy, an NHL survivor. That phrase "NHL survivor" makes her sound like some grizzled, toothless ex-hockey player, when in truth Cindy is anything but. (Ah, acronyms!). We meet at the Green Planet, a local coffee shop down the street from our house.

Cindy’s NHL is similar to mine and David’s – the follicular type. She is in remission now, having received heavy doses of chemotherapy, the same CHOP-R regimen. Her first symptom was an enlarged lymph node in her neck. Surgery to remove the entire lymph node for study was easily accomplished. Cindy points out her scar: which is so inconspicuous, no one who wasn’t looking for it would ever notice.

Like David, Don and Charlotte, Cindy’s and Steve’s testimony is immensely helpful. I can’t say we leave that place feeling comforted, exactly – for she is utterly realistic about the difficult experience of chemotherapy, leading me to dread what lies ahead – but knowledge is power, and the more our knowledge increases, the more the meager power we have at our disposal likewise grows.

Cindy was living in California when she was diagnosed. She received treatment at the UCLA Medical Center. She switched to Sloan-Kettering for her follow-up care and monitoring, after she and Steve moved cross-country as he accepted the call to the church in New Jersey. She shares the name of her doctor, Paul Hamlin – one more name for my list of possible second-opinion physicians.

Cindy’s take on the chemotherapy experience is more connected with the psychology and the spirituality of it. She speaks of finding ways to "go to a different place" when the going gets tough – to be aware of the world around her, but somehow not feel so strongly connected to it. Her language calls to mind some experiences I’ve had, in places like the dentist’s chair. The last time I was at the dentist, he actually thought I was sleeping for a moment (even though the only anesthetic had been novocaine). It sounds like this is a useful skill to have, for the chemotherapy patient. I wonder if I will be able to practice this when I am lying on my stomach in Dr. Lerner’s office next Thursday for the bone-marrow biopsy, and he’s inserting a needle into my un-anesthetized pelvic bone.

At the end of our time there, the four of us pray, there in the coffee shop, holding hands. Thank God for friends – friends like Steve and Cindy, Don and Charlotte, and David – who do not wait to be called, but who simply come!

Cindy’s NHL is similar to mine and David’s – the follicular type. She is in remission now, having received heavy doses of chemotherapy, the same CHOP-R regimen. Her first symptom was an enlarged lymph node in her neck. Surgery to remove the entire lymph node for study was easily accomplished. Cindy points out her scar: which is so inconspicuous, no one who wasn’t looking for it would ever notice.

Like David, Don and Charlotte, Cindy’s and Steve’s testimony is immensely helpful. I can’t say we leave that place feeling comforted, exactly – for she is utterly realistic about the difficult experience of chemotherapy, leading me to dread what lies ahead – but knowledge is power, and the more our knowledge increases, the more the meager power we have at our disposal likewise grows.

Cindy was living in California when she was diagnosed. She received treatment at the UCLA Medical Center. She switched to Sloan-Kettering for her follow-up care and monitoring, after she and Steve moved cross-country as he accepted the call to the church in New Jersey. She shares the name of her doctor, Paul Hamlin – one more name for my list of possible second-opinion physicians.

Cindy’s take on the chemotherapy experience is more connected with the psychology and the spirituality of it. She speaks of finding ways to "go to a different place" when the going gets tough – to be aware of the world around her, but somehow not feel so strongly connected to it. Her language calls to mind some experiences I’ve had, in places like the dentist’s chair. The last time I was at the dentist, he actually thought I was sleeping for a moment (even though the only anesthetic had been novocaine). It sounds like this is a useful skill to have, for the chemotherapy patient. I wonder if I will be able to practice this when I am lying on my stomach in Dr. Lerner’s office next Thursday for the bone-marrow biopsy, and he’s inserting a needle into my un-anesthetized pelvic bone.

At the end of our time there, the four of us pray, there in the coffee shop, holding hands. Thank God for friends – friends like Steve and Cindy, Don and Charlotte, and David – who do not wait to be called, but who simply come!

December 7, 2005 - The Cancer Underground

This evening, Claire and I go to dinner at the home of Don and Charlotte, members of our church. Don is in his 70s and has NHL, of a different variety than my own. Like David, he received stem-cell replacement therapy (at Hackensack Hospital rather than Sloan-Kettering), after his chemotherapy failed to turn back the disease’s assault, and is now in remission. Don had phoned me immediately upon hearing of my diagnosis, and insisted that we come for dinner. He told me he and Charlotte had much they wanted to share with us.

We feel enfolded by warmth and caring. As David did the day before, Don also shares valuable insights about coping with the disease – and, although some of what he says parallels things David told me, it is immensely helpful for Claire to hear all of it. Charlotte describes the predictable cycles of chemotherapy, from her viewpoint as the wife of a patient: a daylong treatment, followed by a week of weakness, then a week of even more severe weakness, then finally a week of relative normality, before the whole cycle begins over again. Charlotte has a name for that third week: "Party Week," she calls it. For it is only in that week that the drugs’ declining suppression of the immune system allows for normal coming and going in public places. I have a fleeting vision of a roomful of hairless people with party hats, dancing around and sounding New Year’s noisemakers.

I wonder how closely my experience with chemo will parallel Don’s – and how that will affect my ministry at the church. So much of what I do – in leadership, in teaching, in preaching – is planned out weeks in advance. Robin and I will have to find some ways to adapt quickly to my down times during the four or five months of my treatments, especially as those down times arrive unexpectedly.

At one point, Don opens his shirt and shows us his porta-cath. It is a pronounced bump on the skin, about the size of a walnut – not the clunky plastic apparatus I had expected (the porta-caths I’ve previously seen have been of a different type, apparently). It looks more like a part of him than what I had seen before. I can see why Dr. Lerner said patients can swim with this sort of device, if they want to. Seeing the thing makes it appear less intimidating.

Sitting there with Don and Charlotte, and recalling my conversation with David of the day before, it feels almost like we’ve made contact with some sort of secret society. We’ve joined the Cancer Underground. I now have the dubious distinction of having been recommended for membership in this highly selective group. Don and Charlotte’s home feels like some kind of safe house. The information they share with us is only for the initiated. It is only when you have this disease that you are ready to hear it.

We feel enfolded by warmth and caring. As David did the day before, Don also shares valuable insights about coping with the disease – and, although some of what he says parallels things David told me, it is immensely helpful for Claire to hear all of it. Charlotte describes the predictable cycles of chemotherapy, from her viewpoint as the wife of a patient: a daylong treatment, followed by a week of weakness, then a week of even more severe weakness, then finally a week of relative normality, before the whole cycle begins over again. Charlotte has a name for that third week: "Party Week," she calls it. For it is only in that week that the drugs’ declining suppression of the immune system allows for normal coming and going in public places. I have a fleeting vision of a roomful of hairless people with party hats, dancing around and sounding New Year’s noisemakers.

I wonder how closely my experience with chemo will parallel Don’s – and how that will affect my ministry at the church. So much of what I do – in leadership, in teaching, in preaching – is planned out weeks in advance. Robin and I will have to find some ways to adapt quickly to my down times during the four or five months of my treatments, especially as those down times arrive unexpectedly.

At one point, Don opens his shirt and shows us his porta-cath. It is a pronounced bump on the skin, about the size of a walnut – not the clunky plastic apparatus I had expected (the porta-caths I’ve previously seen have been of a different type, apparently). It looks more like a part of him than what I had seen before. I can see why Dr. Lerner said patients can swim with this sort of device, if they want to. Seeing the thing makes it appear less intimidating.

Sitting there with Don and Charlotte, and recalling my conversation with David of the day before, it feels almost like we’ve made contact with some sort of secret society. We’ve joined the Cancer Underground. I now have the dubious distinction of having been recommended for membership in this highly selective group. Don and Charlotte’s home feels like some kind of safe house. The information they share with us is only for the initiated. It is only when you have this disease that you are ready to hear it.

December 6, 2005 - Help From David

Today the networking begins in earnest. I spend an hour and half visiting with David, pastor of a nearby Presbyterian Church. David is about the same age as me, and is himself an NHL survivor, now three years into remission. Like me, he has the follicular form of the disease – although he also had one of the more aggressive varieties in addition to it (it’s uncommon for one person to have more than one type, he tells me).

David was very seriously ill indeed, several years ago. He almost died, and was saved at the eleventh hour by stem-cell replacement therapy at Sloan-Kettering. I hang on his every word, for his experience is the closest thing I have seen to a road map of what’s ahead (I hope the herculean effort of stem-cell replacement will not be part of my journey, although it could be). David is particularly helpful in sketching out the various side effects of chemotherapy. He had the same "CHOP-R" (the CHOP chemotherapy cocktail, plus Rituxan) that Dr. Lerner is recommending for me.

In theological debates in presbytery meetings, David and I have not always found ourselves on the same side of the aisle. On many of the more controversial issues that divide our denomination, he is a conservative, and I am a liberal. But that matters little now. We are in this together.

In a prior telephone conversation, I had told David of my diagnosis and of my interest in going to Memorial Sloan-Kettering for a second opinion. He has already put a call in to his personal physician, Dr. Craig Moskowitz, who is on the staff of that hospital. I appreciate this most of all, and tell him so.

I leave more hopeful than when I arrived.

David was very seriously ill indeed, several years ago. He almost died, and was saved at the eleventh hour by stem-cell replacement therapy at Sloan-Kettering. I hang on his every word, for his experience is the closest thing I have seen to a road map of what’s ahead (I hope the herculean effort of stem-cell replacement will not be part of my journey, although it could be). David is particularly helpful in sketching out the various side effects of chemotherapy. He had the same "CHOP-R" (the CHOP chemotherapy cocktail, plus Rituxan) that Dr. Lerner is recommending for me.

In theological debates in presbytery meetings, David and I have not always found ourselves on the same side of the aisle. On many of the more controversial issues that divide our denomination, he is a conservative, and I am a liberal. But that matters little now. We are in this together.

In a prior telephone conversation, I had told David of my diagnosis and of my interest in going to Memorial Sloan-Kettering for a second opinion. He has already put a call in to his personal physician, Dr. Craig Moskowitz, who is on the staff of that hospital. I appreciate this most of all, and tell him so.

I leave more hopeful than when I arrived.

December 5, 2005 - Numbering the Days

Mondays are usually my day off, but today I have a funeral to conduct, in a local funeral home. The service is for a man my own age, a former member of our church, who died of chronic liver problems. His wedding had been the second one I’d performed here in this church, fifteen years ago. I had visited him in recent days in intensive care.

I go through the motions of the funeral liturgy. I imagine I’m doing an adequate job – although inside me there is an odd feeling, an awareness that everything is different now.

The timeworn words of the liturgy and of the scripture passages take on a whole new poignancy for me, even as I speak them. As Psalm 90:12 puts it, I am now "numbering my days," in a way I never have before. Will I gain "a wise heart," as a result?

After the service, the father of the deceased thanks me, and expresses particular appreciation for my being there, in light of the news I’d just received. I had made no mention of my personal health situation during the funeral service, and he had not been in our church the day before, when I'd made my announcement. How had he known? News travels fast in a small town.

I go through the motions of the funeral liturgy. I imagine I’m doing an adequate job – although inside me there is an odd feeling, an awareness that everything is different now.

The timeworn words of the liturgy and of the scripture passages take on a whole new poignancy for me, even as I speak them. As Psalm 90:12 puts it, I am now "numbering my days," in a way I never have before. Will I gain "a wise heart," as a result?

After the service, the father of the deceased thanks me, and expresses particular appreciation for my being there, in light of the news I’d just received. I had made no mention of my personal health situation during the funeral service, and he had not been in our church the day before, when I'd made my announcement. How had he known? News travels fast in a small town.

December 4, 2005 - Telling the Church

The plan I had pre-arranged with Bill swings into action. At 8 a.m. I convene our special Session meeting. Bill has offered to be there, and his presence at the table – especially at that early hour – communicates that something important is afoot.

I come right out and tell the Session members, in much the same way as I did for our kids. They express a wide range of emotions: love, concern, support, anger, dismay. They promise to be there for me, to do what needs to be done. There are times when I’ve seen the Church of Jesus Christ at its best, and this is one of those times. After a while, I leave the meeting and ask Robin to take over the moderatorial duties, so the Session members can ask Bill any questions they need to ask, without me present. I know he’s prepared to share some necessary information, about matters such as the disability provisions of the Presbyterian Pension and Benefits Plan. Who knows if it will come to that? But I would prefer not to be there, as that subject comes up.

During the announcements preceding each of the two worship services, I drop my bombshell. This is more emotional than the Session meeting – it’s worship, after all, that time when God’s people gather. This is among the hardest of things I’ve ever had to do in a worship service, and I expect my discomfort comes across in my tone of voice, my whole presentation. I explain briefly what the disease is all about, and speak of the likelihood of chemotherapy, and the associated down-time that goes along with it. There is so much we just don’t know, I tell the congregation, about what this will all mean for me, and for them. Bill leads the people in a special prayer of intercession.

Fortunately, I’ve had the foresight to ask Robin to preach on this Sunday (one small advantage of the lengthy diagnosis process is that I could pretty well predict when the shoe was going to drop). I don’t think I could have preached today. I assist with the service, but let Robin do most of the big things. As I sit up there, facing the people, I feel more self-conscious than usual. What are they thinking as they look back at me, I wonder? Will they look on me differently from now on – as a sick man, even as a dying man? Suddenly, life is so very different.

Greeting church members at the church door following the service, I experience an outpouring of support. So many people share their love and good wishes. At least a dozen people offer to drive me to medical appointments (a need I had mentioned in passing, when I made my announcement). The body of Christ does what it does best.

I come right out and tell the Session members, in much the same way as I did for our kids. They express a wide range of emotions: love, concern, support, anger, dismay. They promise to be there for me, to do what needs to be done. There are times when I’ve seen the Church of Jesus Christ at its best, and this is one of those times. After a while, I leave the meeting and ask Robin to take over the moderatorial duties, so the Session members can ask Bill any questions they need to ask, without me present. I know he’s prepared to share some necessary information, about matters such as the disability provisions of the Presbyterian Pension and Benefits Plan. Who knows if it will come to that? But I would prefer not to be there, as that subject comes up.

During the announcements preceding each of the two worship services, I drop my bombshell. This is more emotional than the Session meeting – it’s worship, after all, that time when God’s people gather. This is among the hardest of things I’ve ever had to do in a worship service, and I expect my discomfort comes across in my tone of voice, my whole presentation. I explain briefly what the disease is all about, and speak of the likelihood of chemotherapy, and the associated down-time that goes along with it. There is so much we just don’t know, I tell the congregation, about what this will all mean for me, and for them. Bill leads the people in a special prayer of intercession.

Fortunately, I’ve had the foresight to ask Robin to preach on this Sunday (one small advantage of the lengthy diagnosis process is that I could pretty well predict when the shoe was going to drop). I don’t think I could have preached today. I assist with the service, but let Robin do most of the big things. As I sit up there, facing the people, I feel more self-conscious than usual. What are they thinking as they look back at me, I wonder? Will they look on me differently from now on – as a sick man, even as a dying man? Suddenly, life is so very different.

Greeting church members at the church door following the service, I experience an outpouring of support. So many people share their love and good wishes. At least a dozen people offer to drive me to medical appointments (a need I had mentioned in passing, when I made my announcement). The body of Christ does what it does best.

December 3, 2005 - Telling Family

I call my mother in the morning. She acts as shocked as Jim and Dave did. The news is so big, she seems to have a hard time taking in all the details. Sensing denial – that predictable side-effect of life-shaking experiences – I carefully repeat several key points. After the call, I send her an e-mail putting some of the facts into writing, including also some links to a few medical web pages. It is, indeed, a lot to take in all at once.

Claire calls a couple of her sisters, and asks them to spread the word to the rest of the family. She tells her sister Eva, and also Eva’s kids, Cory and Elizabeth. I phone my cousin Eric, and ask him to tell his side of the family.

I phone Min, our church’s Clerk of Session (the Session is the local church’s governing board in the Presbyterian system). I tell her my news, and tell her I’m calling a special Session meeting for the next morning. I ask her to phone her fellow Elders – asking her not to state the reason for the meeting, just to say it’s important. (This is something I prefer to tell the Session members myself.)

There is no game plan for how to do this sort of thing. Our denominational constitution, the Book of Order, offers no help for such a fundamentally disordered situation. Were I accepting a call to another church, there are well-thought-out procedures to follow. But for a pastor trying to figure out how to tell the church’s elected leadership about a newly-diagnosed, life-threatening illness, there is no guidance. Common sense is the only guide.

I phone Lynn, our church’s Personnel Committee chair, a psychological counselor by profession. She expresses shock and grief, and offers emotional support. She marvels at the way I am delivering this information so dispassionately. I second-guess myself, after concluding the conversation with her. How am I dealing with this, after all? Am I adequately in touch with my feelings? In making all these calls, in fulfilling my responsibilities as pastor and moderator of the Session, am I merely covering up my pain with a veneer of task-oriented competence?

No, I conclude. I’m having a hard enough time with this, but I’m simply enacting a plan I’d worked out ahead of time, in consultation with Bill, our executive presbyter. Lynn and others are hearing this news for the first time; I’ve had several weeks to come to terms with it.